Jacek Karpiński: the engineer who built the most modern microcomputer in the 70’s

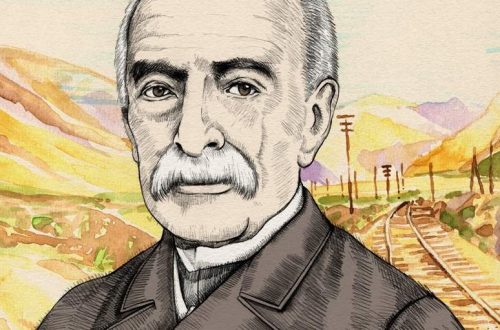

Wanda Karpińska was expecting a baby, and Adam Karpiński wanted his son to be born at the peak of Mont Blanc. In April 1927, the bad weather wasn’t conducive for the daredevil expedition, so Wanda and Adam descended from the Alps on the Italian side and their son Jacek was born in Turin.

When the Second World War broke out, Jacek Karpiński was in the sixth grade. Nonetheless, during the siege of Warsaw in September 1939 he was a liaison serving the anti-aircraft defenses of city center. Soon thereafter, during the German occupation, he set up a gun range and a created weapons cache in his own basement.

I was greatly impressed by his story about how he and his brother Marek played chess and waged sea battles as children. They fought their wars for long hours. They tirelessly captured pawns and queens, sank each other’s ships until bloodless skirmishes finally proved which of them was the better strategist. But they played differently than most: no boards or pieces of paper, playing only in memory. Battles rolled over in their heads. They moved pawns in their minds, captured pieces and put kings in check. Perhaps thanks to this Jacek trained himself in a specific kind of thinking.

Piotr Lipiński, “BIOGRAFIA KARPIŃSKIEGO, czyli artyści tworzą komputery”, 2014, available in whole here.

Not long after the war, Jacek Karpiński was building a submarine in an isolated shed wanting to sail down the Vistula to the sea and escape from Poland, but ultimately he decided to stay in his motherland and gave up the planned operation. Soon afterwards, he completed his first major project – AAH, a weather forecasting machine.

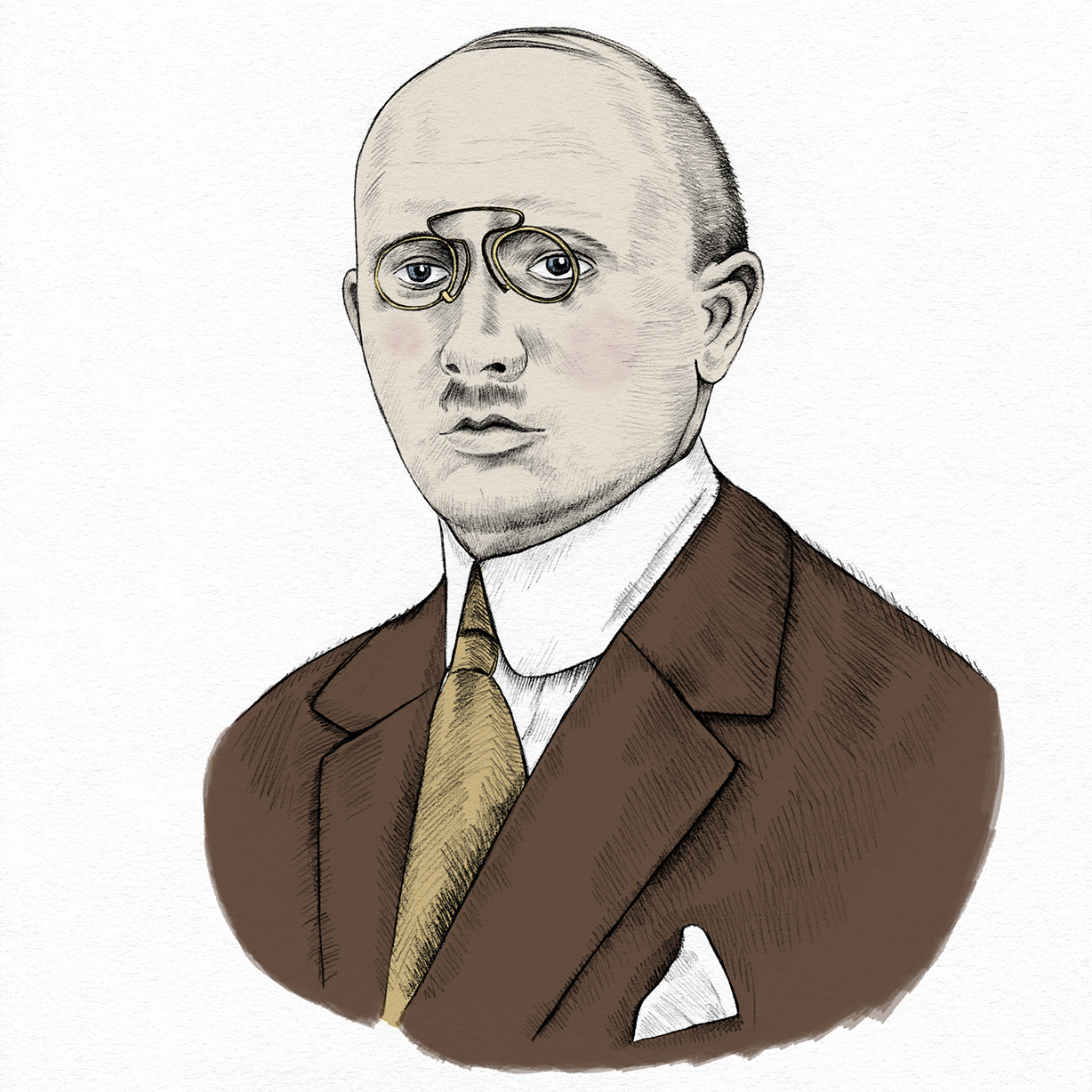

Four years later, in 1959, he completed the construction of the AKAT-1 machine, the world’s first analog computer operating as a transistor analyzer of differential equations. It was far ahead of its time in terms of both operational capabilities and its “sci-fi” design.

AKAT-1 Machine.

In 1959, another computer called AKAT-1 was constructed. (…) It was the first construction of this type in the world.

Dariusz Grałka, “Jacek Karpiński – wynalazca komputera osobistego” [in:] Zeszyty Naukowe WSInf Vol 9, Nr 1, Łódź 2010, p. 56-57, available in whole here.

In the UNESCO competition for young designers Jacek Karpiński represented Poland and was among the six winners selected from among 200 participants. This success allowed him to go to the United States. He was delighted with American laboratories and universities. However, he rejected a very lucrative career opportunity – namely, the position of the president of the Supervisory Board of the Bank for the Development of New Fields of Techniques with an annual salary of 100,000 dollars – and returned to Poland.

The generations of computers abroad were changing like in a kaleidoscope, but we were just spinning our wheels. (…) Only one man did not wait. When minicomputers appeared, Eng. Karpiński well understood what opportunities there were for countries lagging behind in computerization. So he clung to the idea and pressed on, no matter the obstacles.

Grzegorz Biały, “Mini… czy Max”, Tygodnik Ilustrowany Przyjaźń, No. 36, 1971.

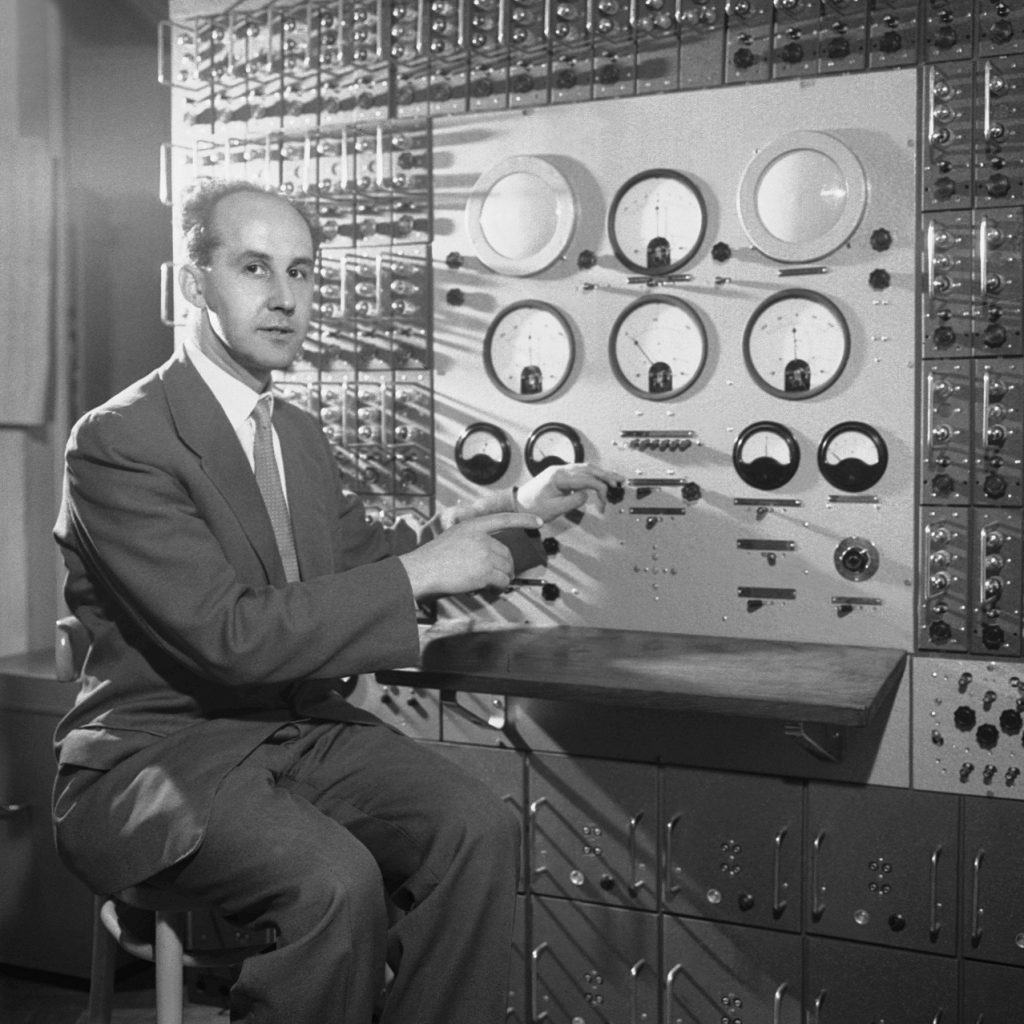

Soon, Jacek Karpiński constructed the world’s second perceptron, a self-learning machine equipped with a camera and capable of recognizing shapes and objects. A short time later, another computer, called the KAR-65, was to be used to scan and analyze photos of electrons and neutrons. The project with the scanner was commissioned by the Institute of Physics at Hoża Street in Warsaw.

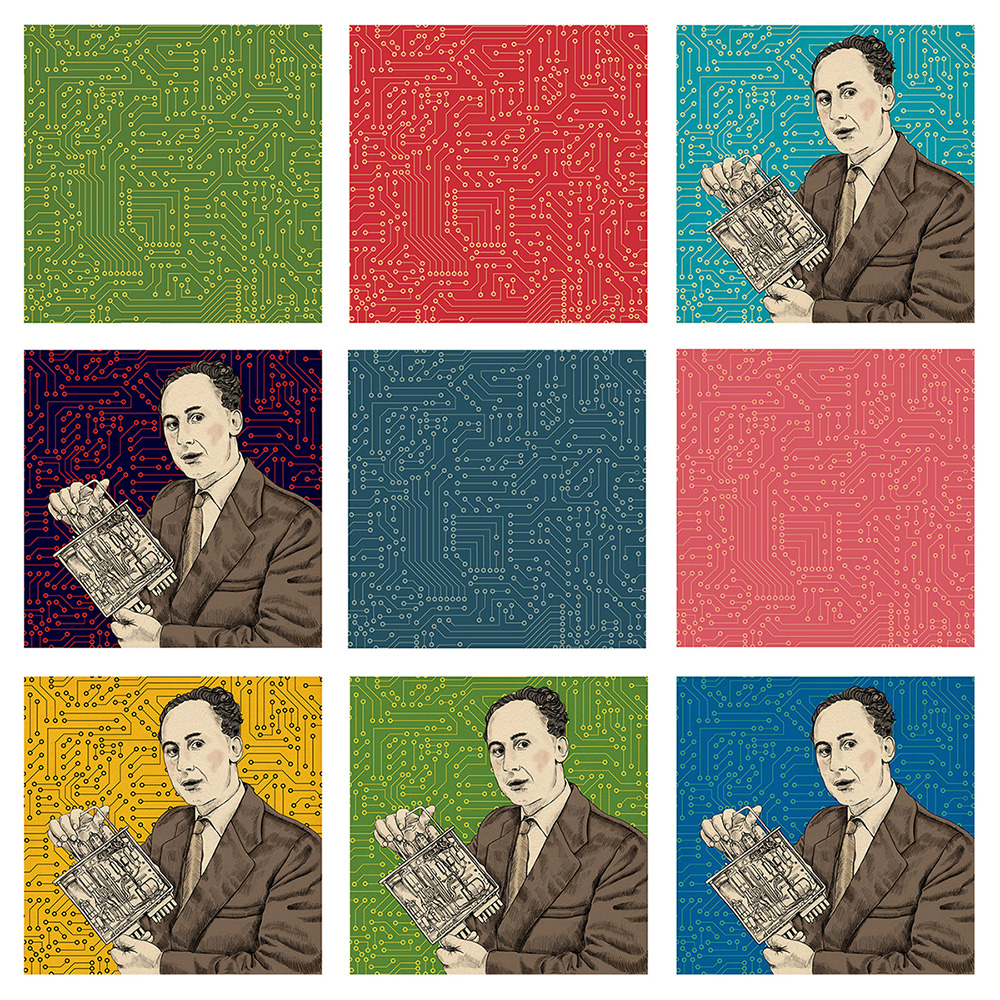

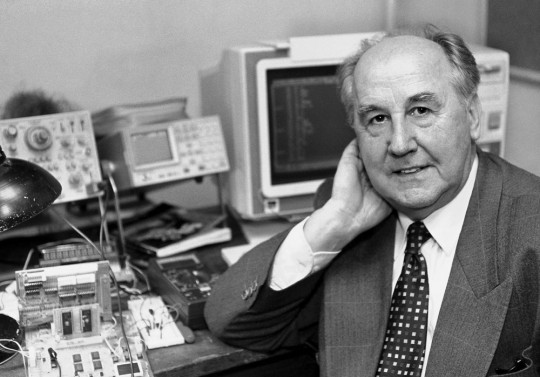

Jacek Karpiński and the KAR-65 computer, image source here.

The nature of this willful individualist and his inability to adapt to the ways of working adopted in the Polish People’s Republic earned Karpiński enemies among both party dignitaries, and – despite his ongoing professional successes – computer constructors, above all, those at the Elwro factory in Wrocław. The then cutting-edge computer “ODRA” produced in Wrocław occupied an entire room and needed another for ventilation, while the KAR-65 made by Jacek Karpiński was smaller and more efficient.

The machine sinks into a trance, we hear a series of rhythms with an almost musical sound, as if Joe Morello himself was knocking them out with the drum brushes; the lights of the desktop are flashing to the beat (…) You have the impression that the machine is dancing the rumba and whistling with great vigor.

Description of the KAR-65 computer in “Trybuna Robotnicza“. Joe Morello playing the drums available to listen here.

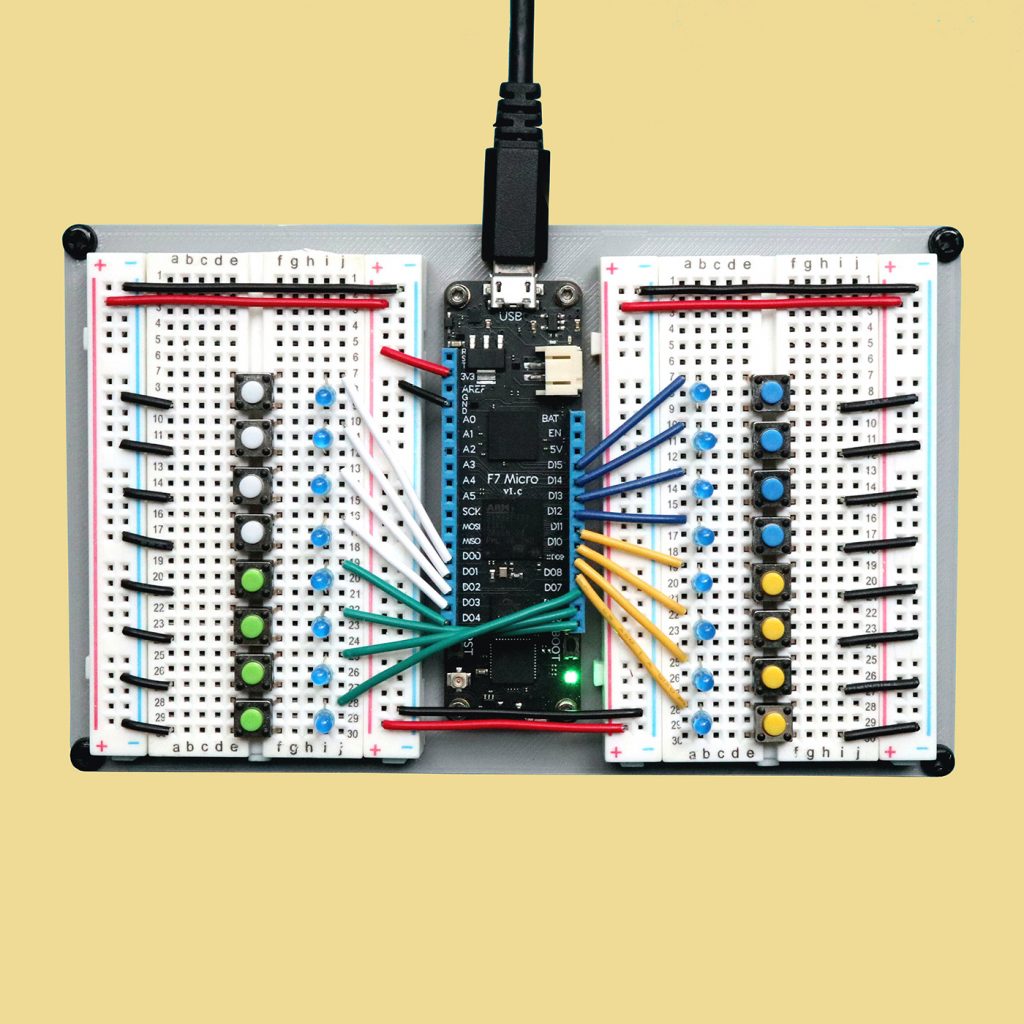

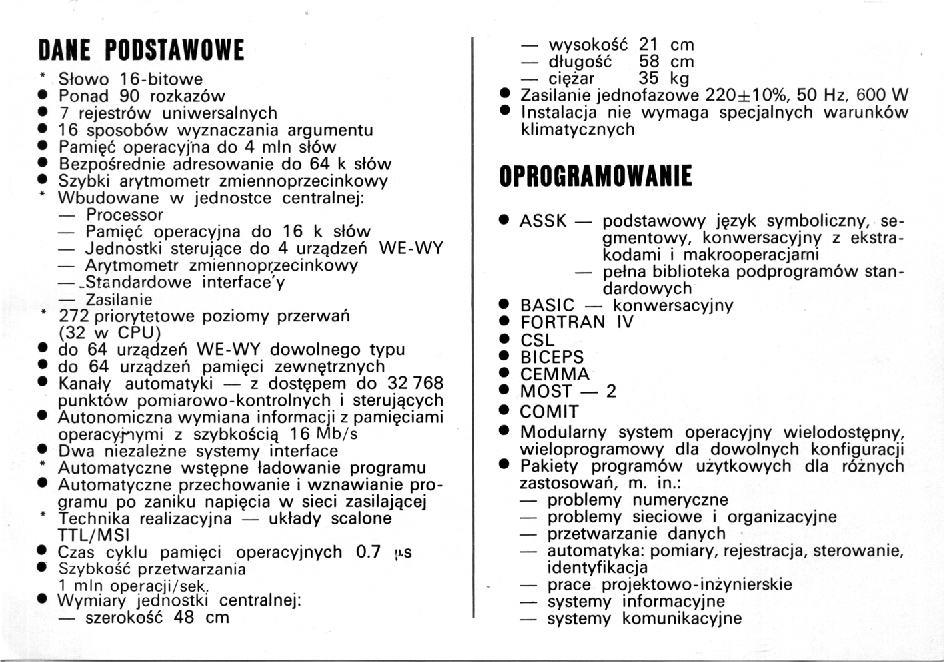

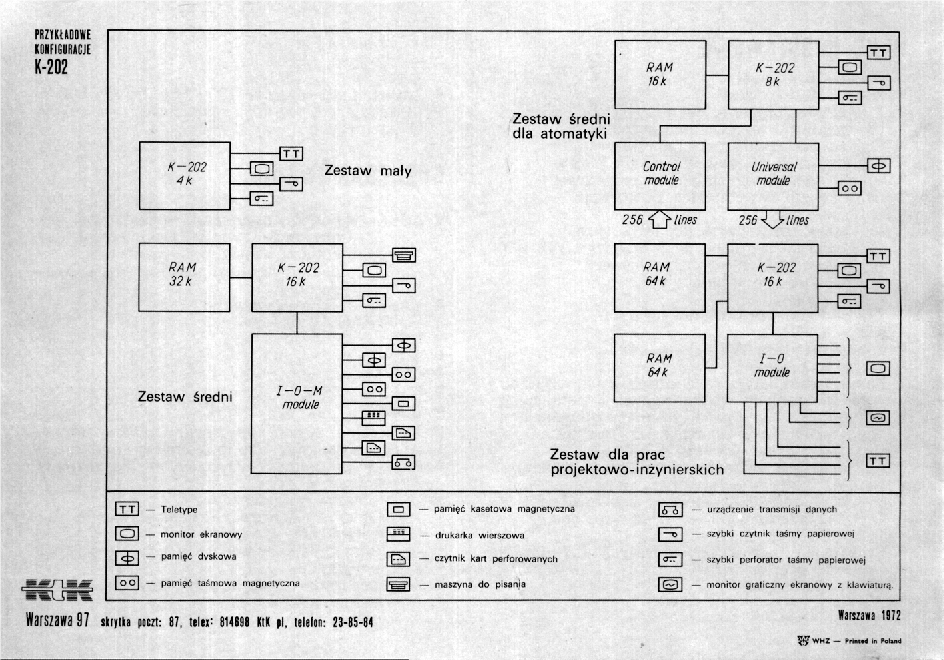

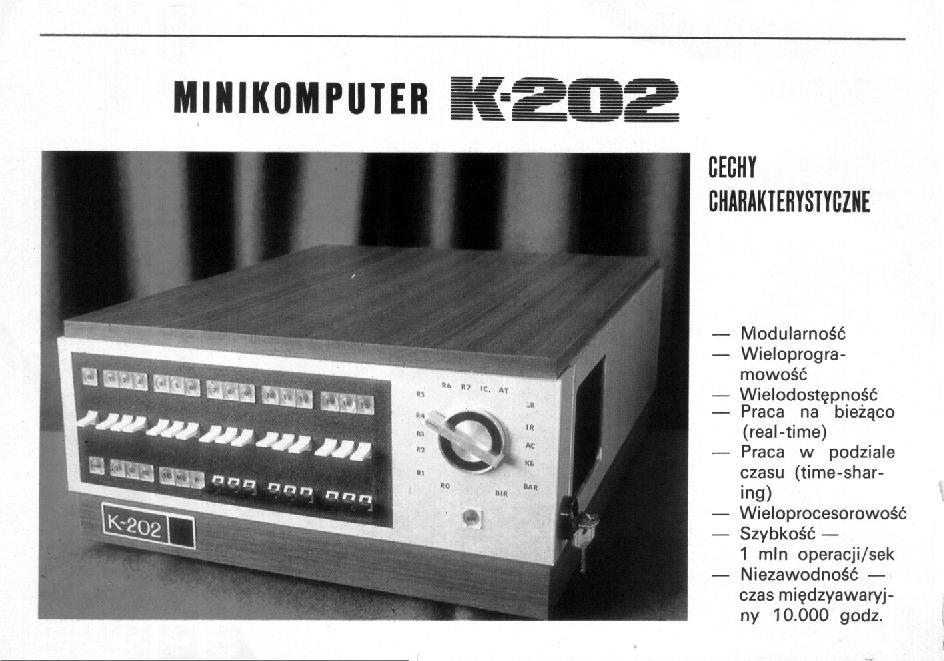

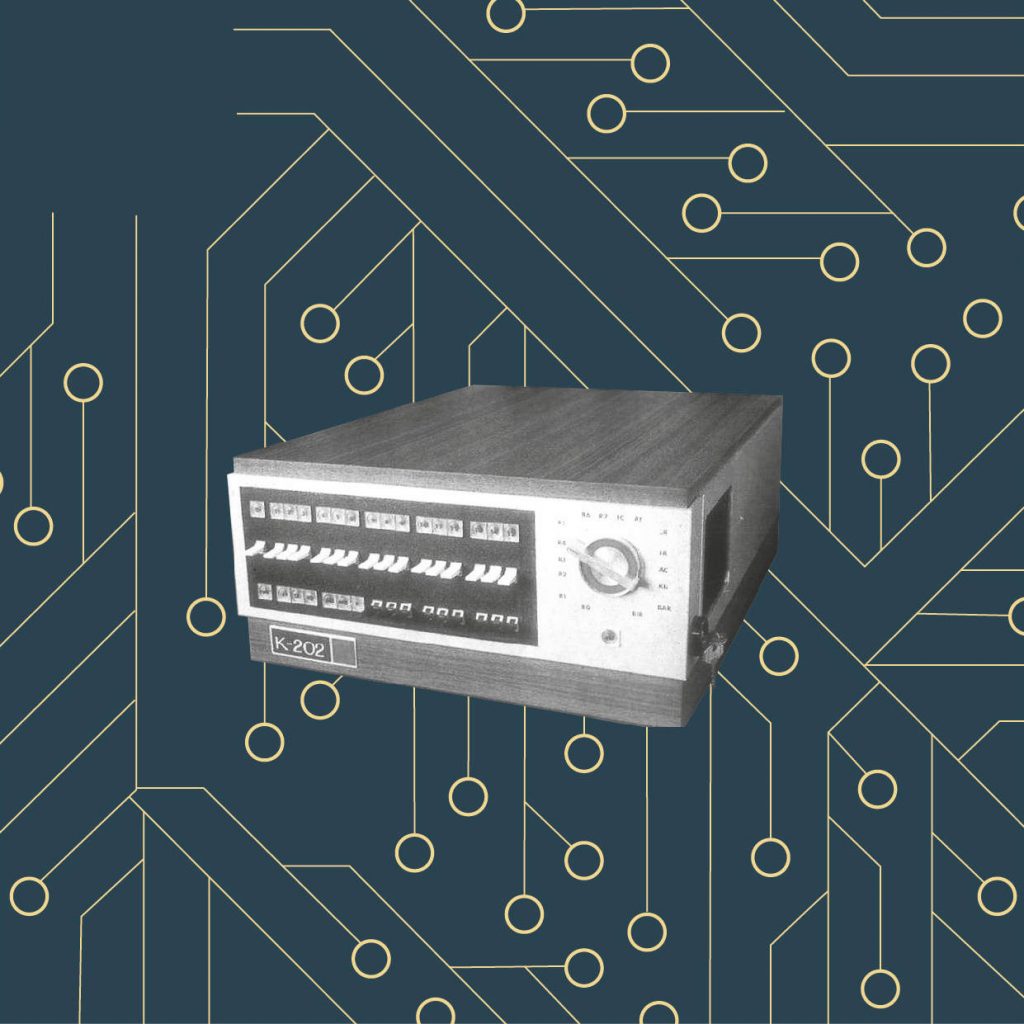

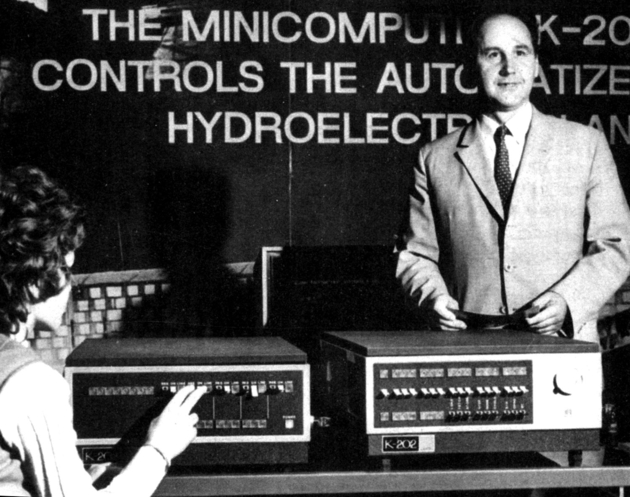

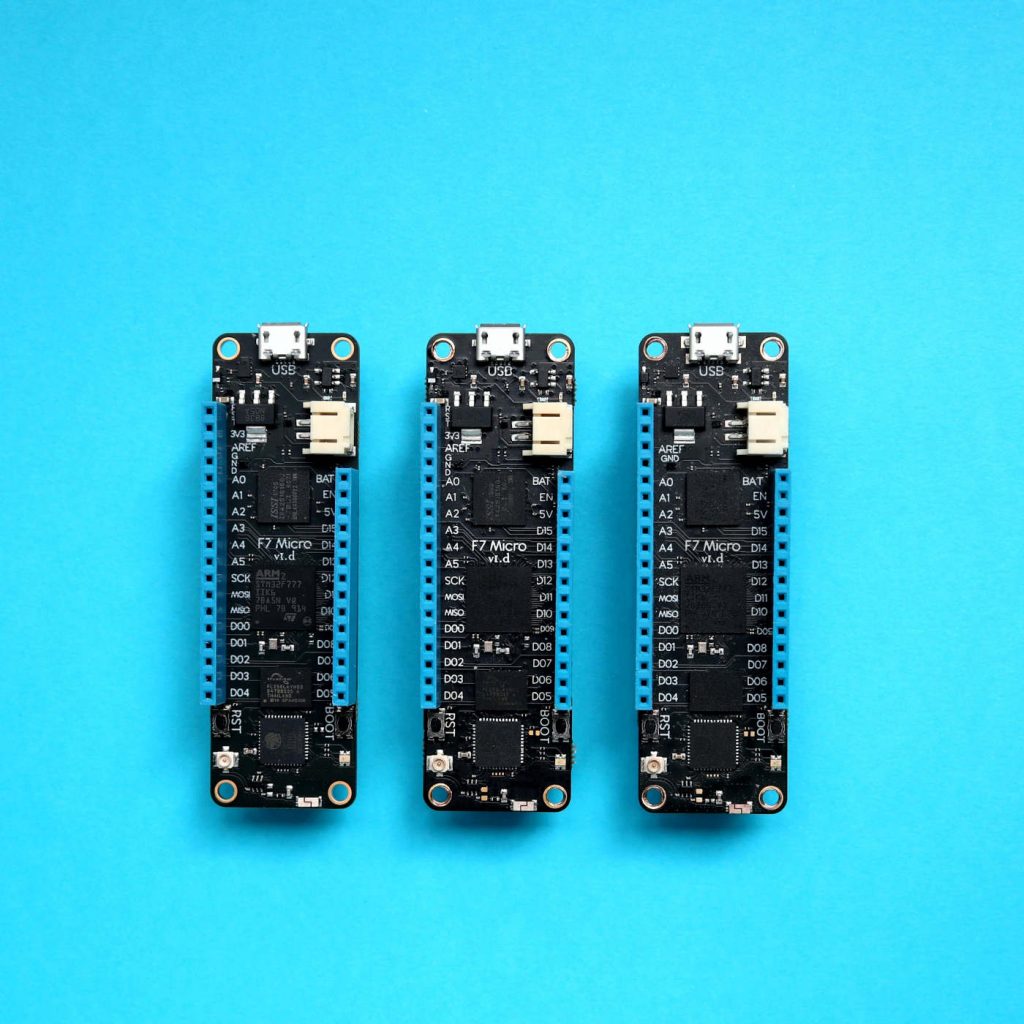

As a prototype, the KAR-65 did not compete with industrially manufactured machines from Elwro plants, but another of Karpiński’s computer – the K-202, which ran faster than computers from even ten years later, and was the size of a suitcase and intended for industrial production – was a powerful threat.

The representatives of the Wrocław-based Elwro plants, which produced the ODRA computer, felt their monopoly was threatened. (…) It was both amusing and worrying when a specialist from Wrocław said that the K-202 is too modern for us. In fact, the K-202 was not too modern for us, but rather the structures in which it could be used were too outdated.

Henryk Boruciński, “Kto następny, czas ucieka…”, Perspektywy No. 26, 1971.

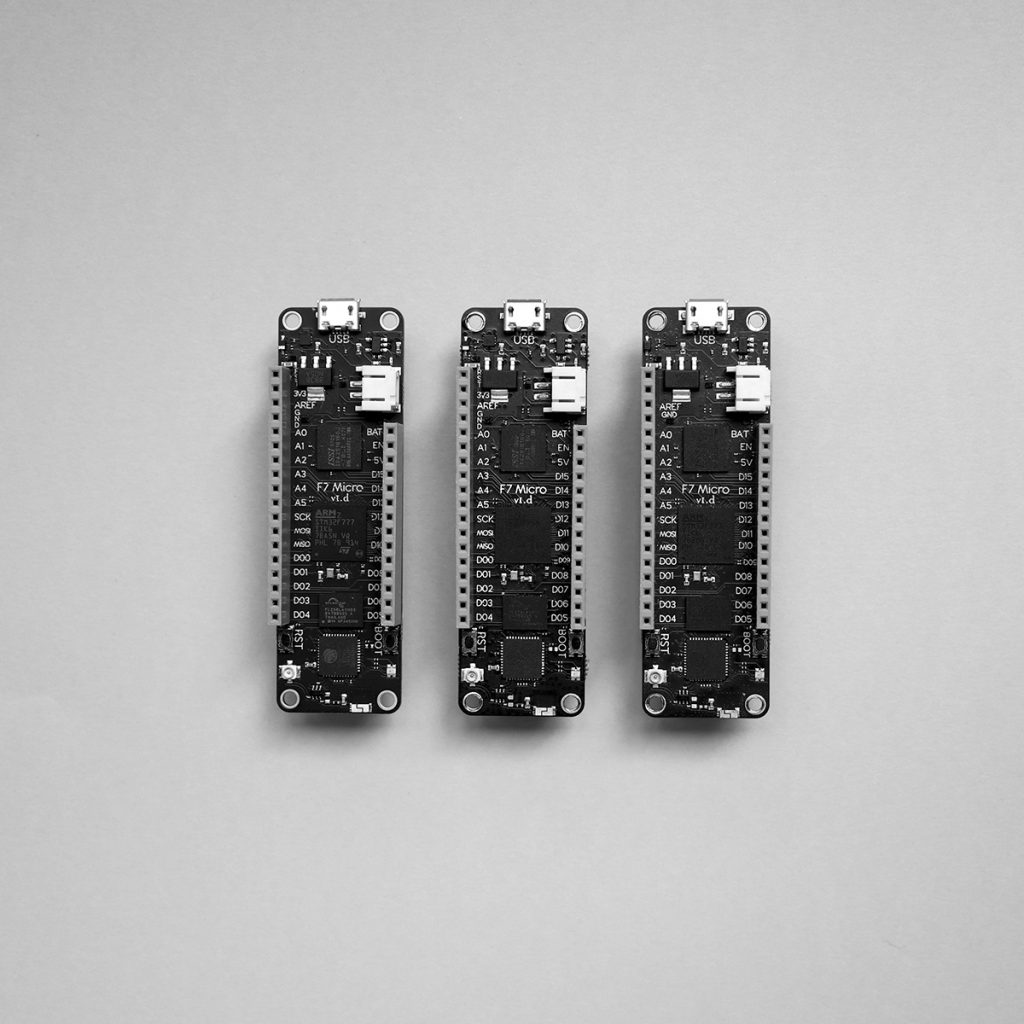

The production of the K-202 computer started in laboratory conditions with the support of British companies DataLoop and MB Metals.

Jacek Karpiński and his team constructed 30 K-202 computers, of which 15, in accordance with the agreement, were shipped to Great Britain, and another 15 were sold to Polish offices and state-owned companies (one computer was privately owned).

At the Computer Exhibition at London’s Olimpia in 1971, the K-202 turned out to be a world-class computer that only American PDP machines could compete with.

Unfortunately, the cooperation with British companies was broken off as a result of the intervention of the communist secret services. Moreover, commercial offers from France and Sweden were rejected, while Jacek Karpiński was expelled from the Institute of Mathematical Machines in Warsaw and blacklisted. In protest, he moved to rural Masuria, where he rented a farm and started breeding hens and pigs.

Jacek Karpiński, forced to abandon his passion, wasn’t really breeding pigs so much as he was continuing his protest. His work in the countryside was a voice of protest: look what computer scientists have to do in Poland today.

Piotr Lipiński, “Geniusz i świnie. Rzecz o Jacku Karpińskim”, Pruszków 2014, p. 202.

His name and surname as well as the name of his greatest work – the K-202 computer – were censored.

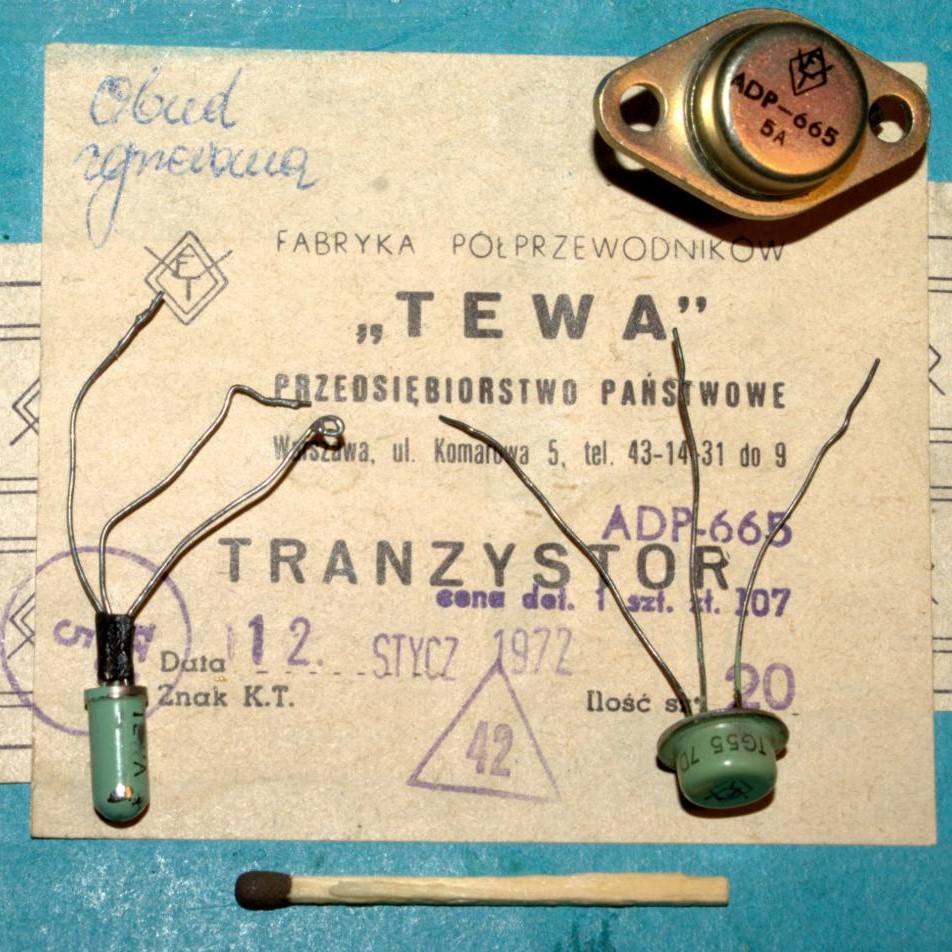

Piotr Lipiński, the author of the biography and the film about Jacek Karpiński, says that after the publication in the Polish Film Chronicle in 1981 of a short report about a genius computer constructor breeding pigs near the town of Olsztyn in Masuria, at concerts of the then very popular in Poland band “Perfect”, instead of the original lirycs “Elektronik kradnie w Tewie” (Pol. An electrician’s stealing in Tewa), people sang “Elektronik grzebie w Chlewie” (Pol. An electrician’s digging in the pigsty”).

Lipiński Piotr, “An electrician’s digging in the pigsty”

Semiconductor Factory “TEWA”

Karpiński accepted the invitation of Stefan Kudelski, an inventor and designer of world-class tape recorders operating in Switzerland, but despite their chemistry, their co-operation did not go well.

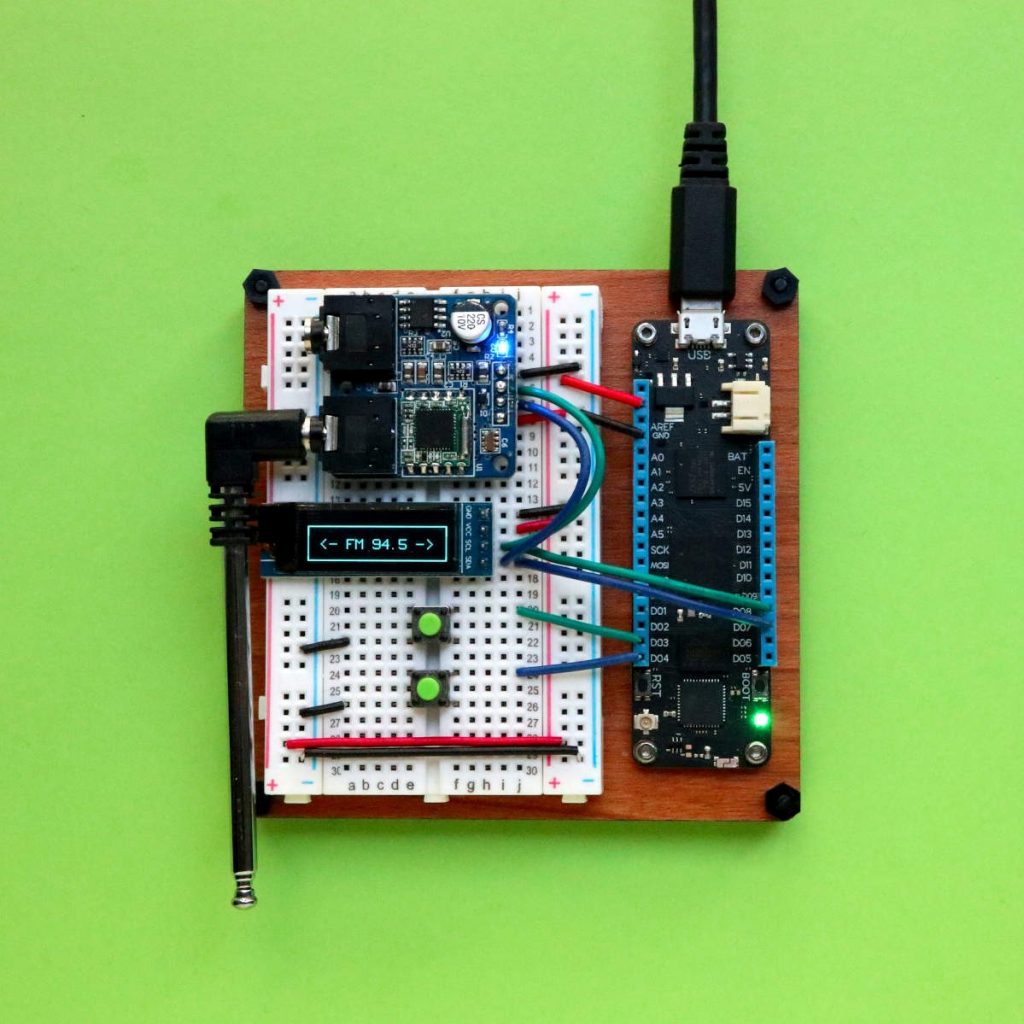

Jacek Karpiński returned to Poland in the 1990s with a pen reader project – a pen-like reader that copied text from paper sources directly into text editors, which saved tedious transcription and could be widely used in many areas and professional work of various professions.

Scanners from that time usually allowed users to import a page of text onto the computer as a graphic, just like we would take a photo. However, they could not convert it into letters. Only OCR software made it possible to” read” and quickly import it into a writing program such as Word. (… ) He designed the device in Switzerland at the request of an accountant who complained that he had to enter a lot of data manually into the computer.

Piotr Lipiński, “Geniusz i świnie. Rzecz o Jacku Karpińskim”, Pruszków 2014, p. 225.

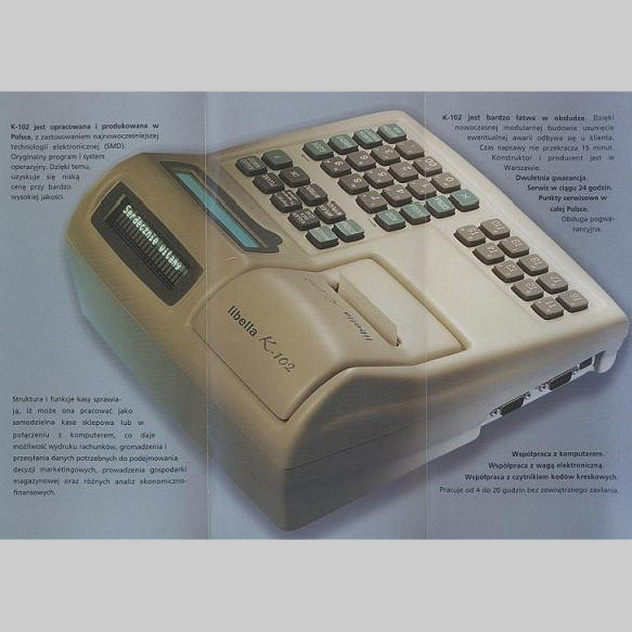

This time, however, a bank stood in the way to success, refusing to pay out a significant part of the loan taken by Karpiński for the device’s production, demanding further loan guarantees apart from already foreseen ones. Later, Karpiński designed a modern cash register, but he did not solve his financial problems this way either.

This cash register was at the time the smallest and most universal cash register in Poland.

The article “Cash register K-102” in gallery of Karpiński’s inventions, source here.

In his retirement, Jacek Karpiński was supplementing his small pension by designing websites. He died in 2010.

Piotr Lipiński, Geniusz i świnie. Rzecz o Jacku Karpińskim, Pruszków 2014, p. 232.

Bibliography and sources:

- Henryk Boruciński, Kto następny, czas ucieka…, Perspektywy Nr 26, rok 1971,

- Grzegorz Biały, Mini… czy Max, Tygodnik Ilustrowany Przyjaźń, Nr 36, 1971,

- Piotr Lipiński, Geniusz i świnie. Rzecz o Jacku Karpińskim, Pruszków 2014,

- Dariusz Grałka, Jacek Karpiński – wynalazca komputera osobistego [in:] Zeszyty Naukowe WSInf Vol 9, Nr 1, Łódź 2010, available in whole here,

- Marek Kępa, The Computer Genius the Communists Couldn’t Stand, 2017, available in whole here.

- Catalogue of the exhibition Niespełnione Nadzieje Polskich Informatyków. W stronę komputera osobistego curated by Andrzej Berezowski,

- Gallery of Jacek Karpiński’s inventions “K-101“,

- Co się stało z polskim Billem Gatesem, the documentary about Jacek Karpiński directed by Piotr Lipiński, available on vod.tvp.pl.

Graphics and illustrations: Małgorzata Bochniarz-Różańska

Text: Filip Jegliński

English version: Filip Jegliński, Philip Steele