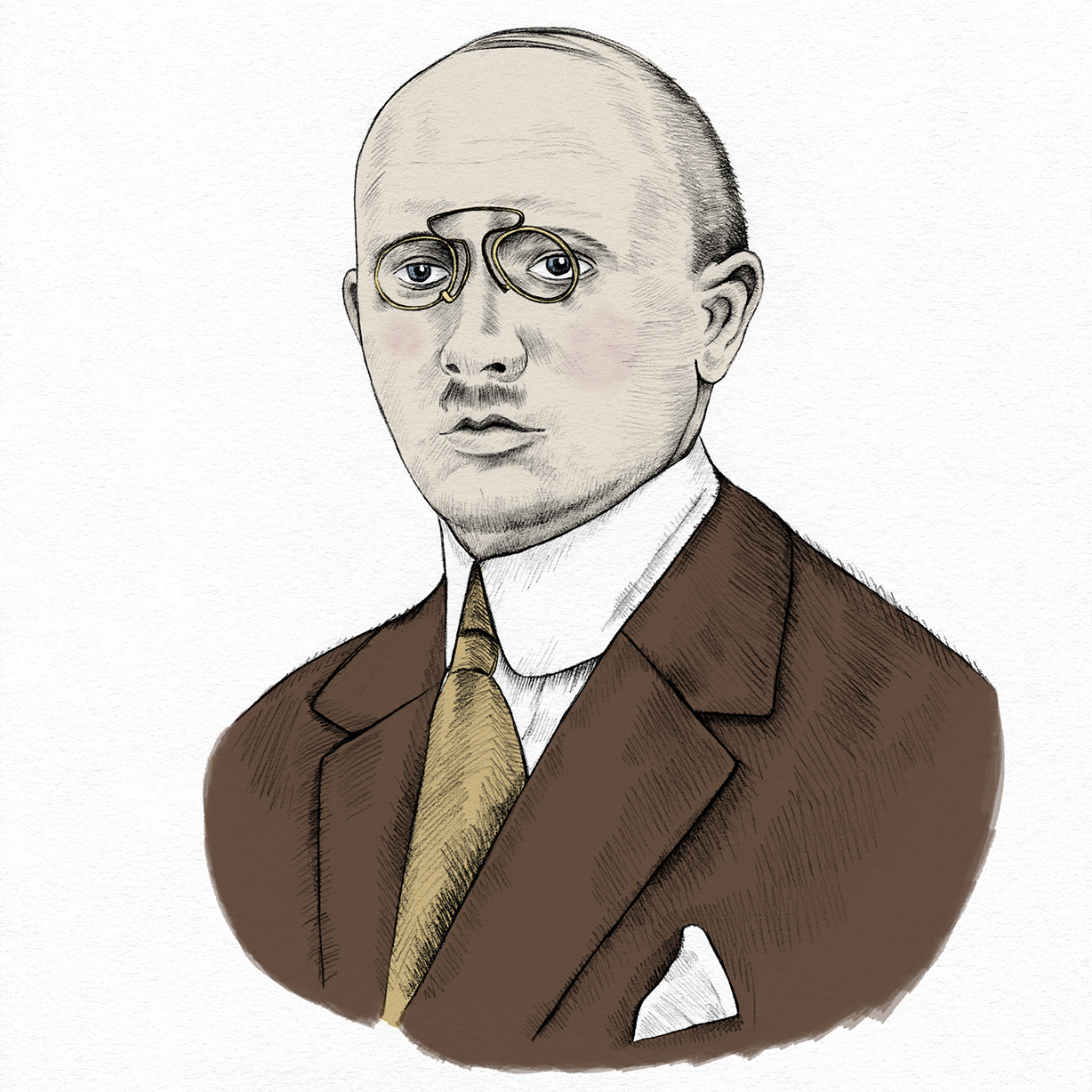

Stefan Bryła, the man who built the world’s first welded bridge and the first Polish skyscrapers

Bryła, the man who wanted to move a chunk of Poland* after the war ended [the word Bryła means chunk]. (…) ‘You have to think, you have to work’ – this was his motto. Today this quotation is written on the boulder next to the bridge over the Słudwia river near Łowicz.

Grabowski M. (2019). Bryła, który chciał po wojnie poruszyć bryłę Polski. Polska Times Historia. Link.

He was 24 years old when he set off on a journey around the world. In 1910 he was sent to the Polytechnic College in Berlin at the request of the Lviv Polytechnic. From Berlin he relocated to the French School of Bridges and Roads, then to the University of London, from where he set off to North America. He studied and worked in Canada and the US, and then returned home through Japan, Korea, China, and Siberia. He wrote many diaries during his travels.

After his American experience, Stefan Bryła specialized, as one of the few European constructors back then, in building skyscrapers (the Polish name for them is a calque from English).

Bielska A., Bielski M. (2011). Przypadek profesora Bryły. Przegląd techniczny. Gazeta inżynierska. Link.

Throughout his scientific journey, he worked on designing and building steel constructions, among them the Woolworth Building in New York in 1912.

It was the first time he saw a high-riser. He was one of the engineers who worked on the construction of the Woolworth Building in New York. The building is 241 meters tall and was the highest construction in the world until 1930, when the Chrysler Building surpassed it.

Polskie Radio. Stefan Bryła. Innowacyjny konstruktor mostów i wieżowców. Link.

Stefan Bryła was born in Kraków in 1886. He graduated from the real school in Stanisławów and then – at only 22 years old – he received a diploma with honours from the Faculty of Civil and Water Engineering at the Lviv Polytechnic. A year later, he obtained a PhD in technical sciences and in the following year (1910) he habilitated.

The engineer must be creative, must create new works, new forms. He cannot be a slave to other people’s thoughts. (…) In our profession, we should be pursuing Polish engineering in such a way, that it serve our country and our needs. In such a way that it shines with its own light, thanks to the efforts of our thoughts, but unlike the Moon, that reflects only an anemic light.

Bryła S. (1937). Germanizowanie techniki polskiej.

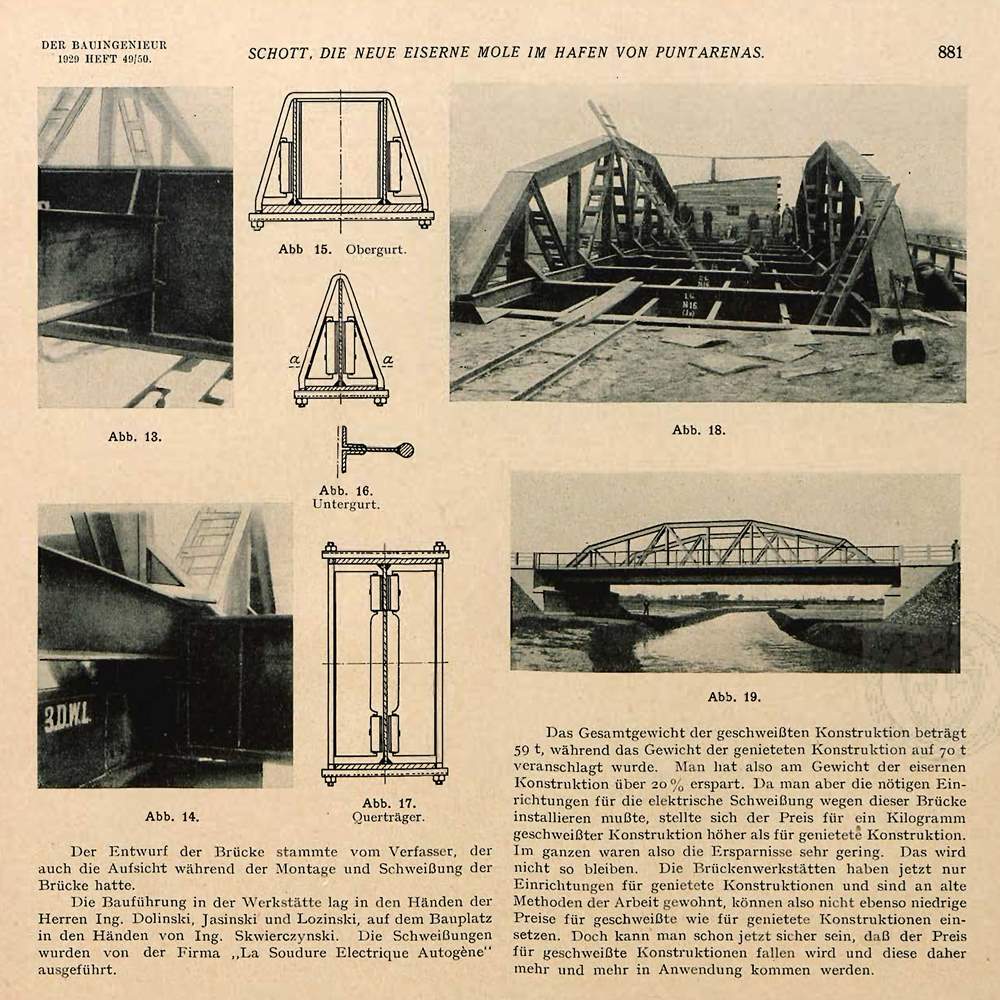

At the beginning of the 20th century, bridges were constructed with the use of rivets.

New ideas often give rise to heated polemics before they become popular. This was illustrated in the ‘holy wars’ that took place at the Warsaw Technical University in the early ‘30s, between the honored metal engineering specialist Professor Andrzej Pszenicki (1869-1941), the author of many interesting railway and road bridge projects in Poland and Russia, and Professor Stefan Bryła. Professor Pszenicki used to ask students who were undecided which specialization they want to choose, and he did so in a playful way, with a touch of irony: ‘Riveting – it’s sewing, welding – it’s gluing. What kind of clothes do you prefer? Sewn or glued?’

Bielska A., Bielski M. (2011). Przypadek profesora Bryły. Przegląd techniczny. Gazeta inżynierska. Link.

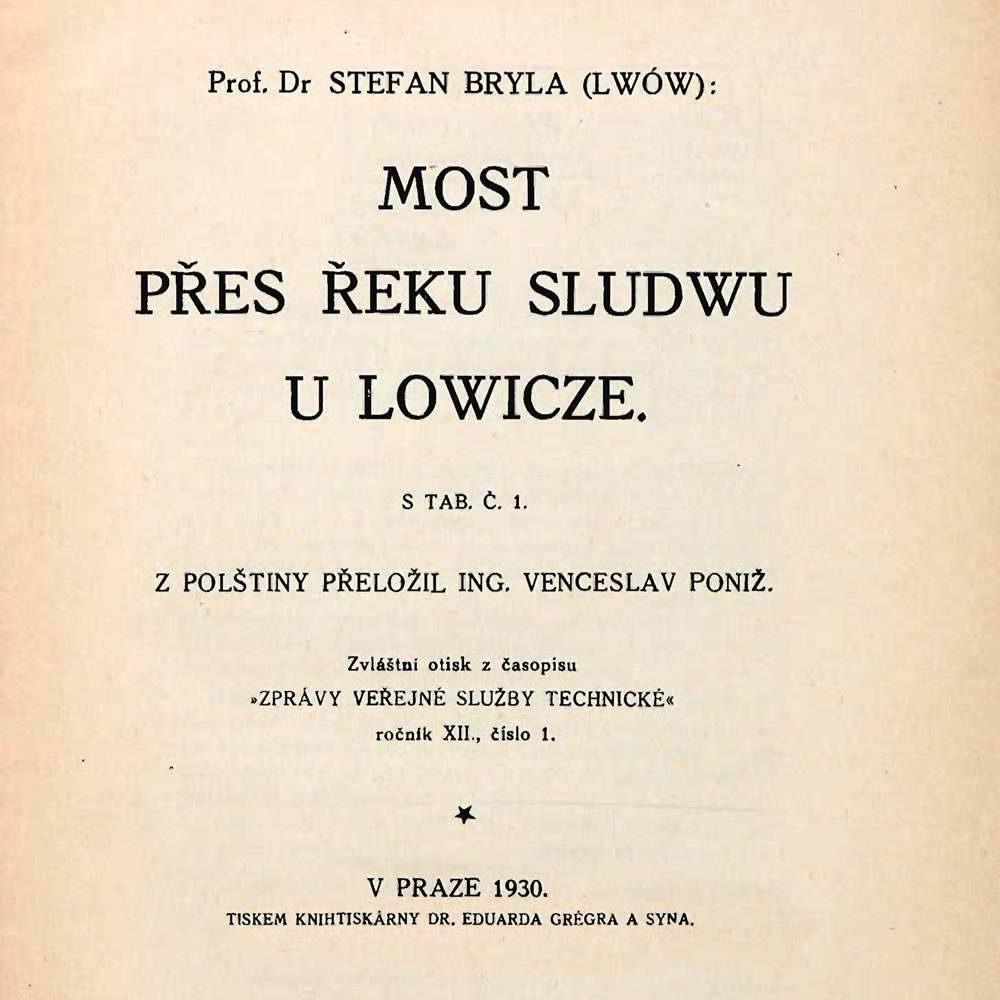

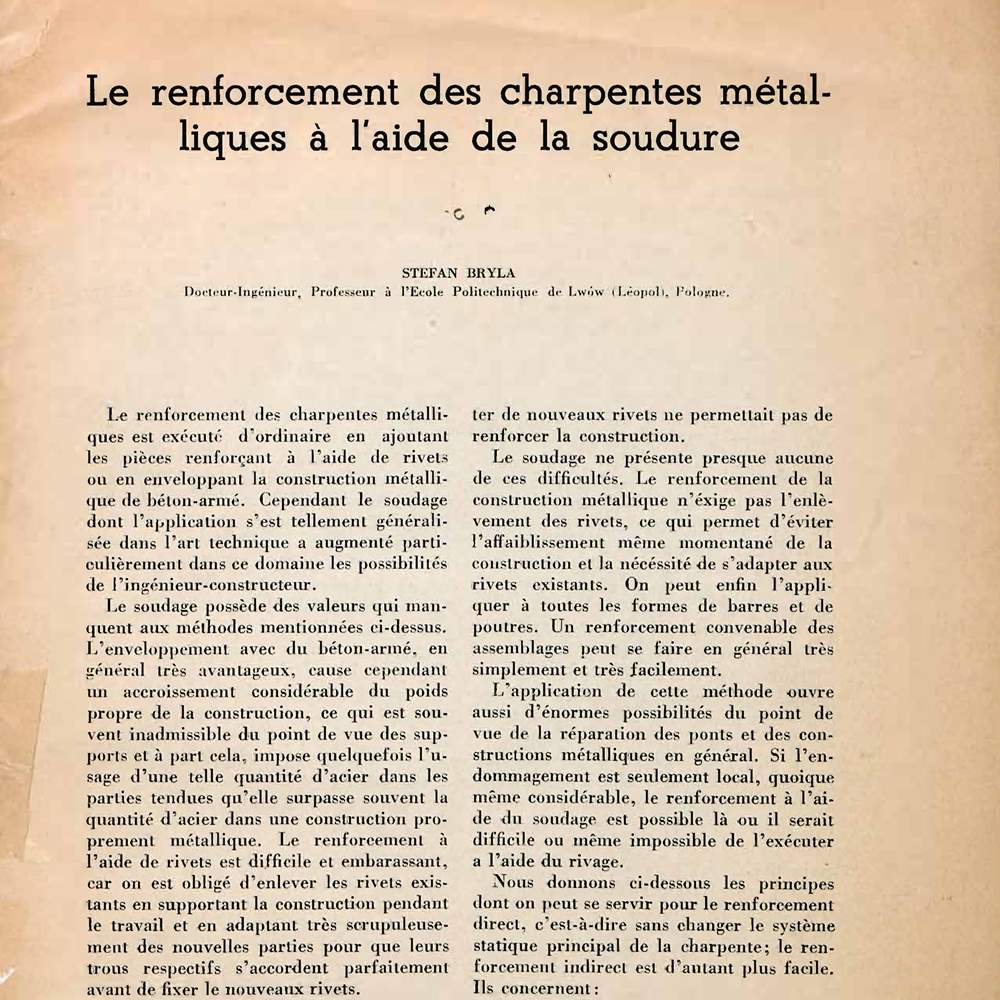

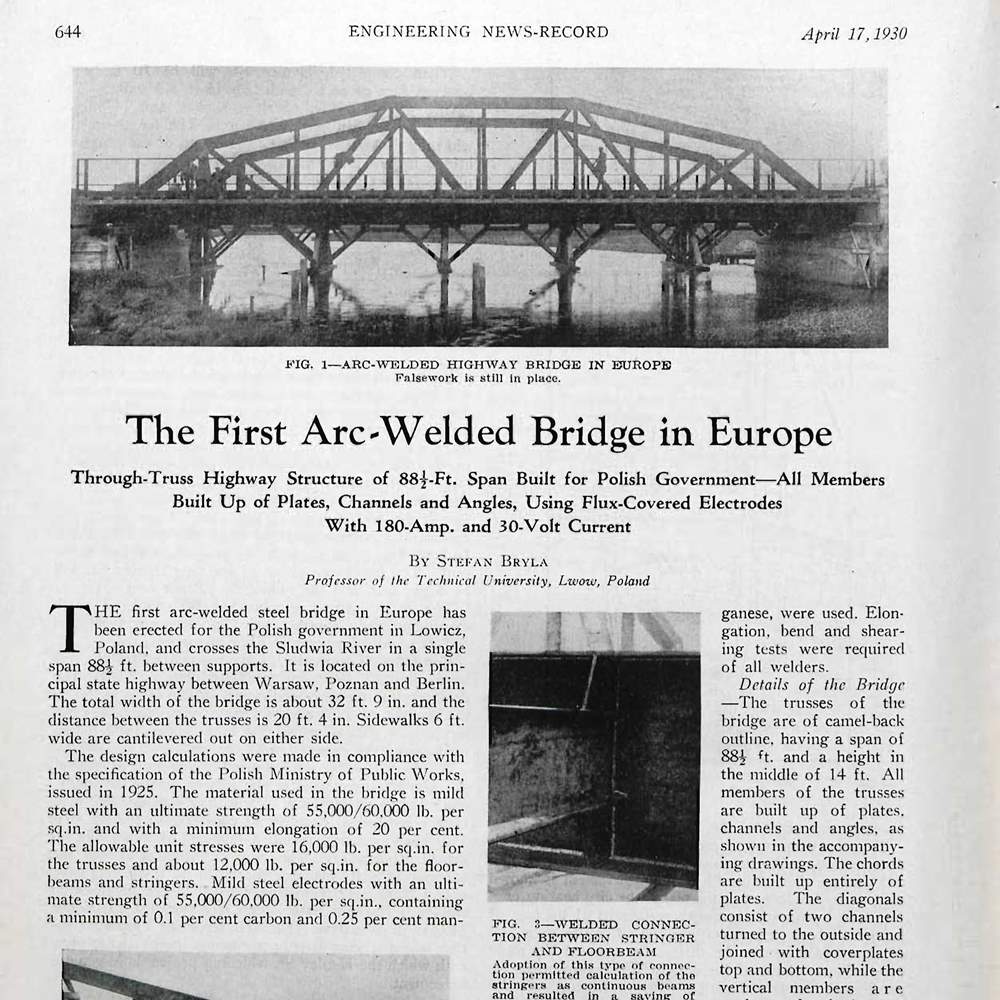

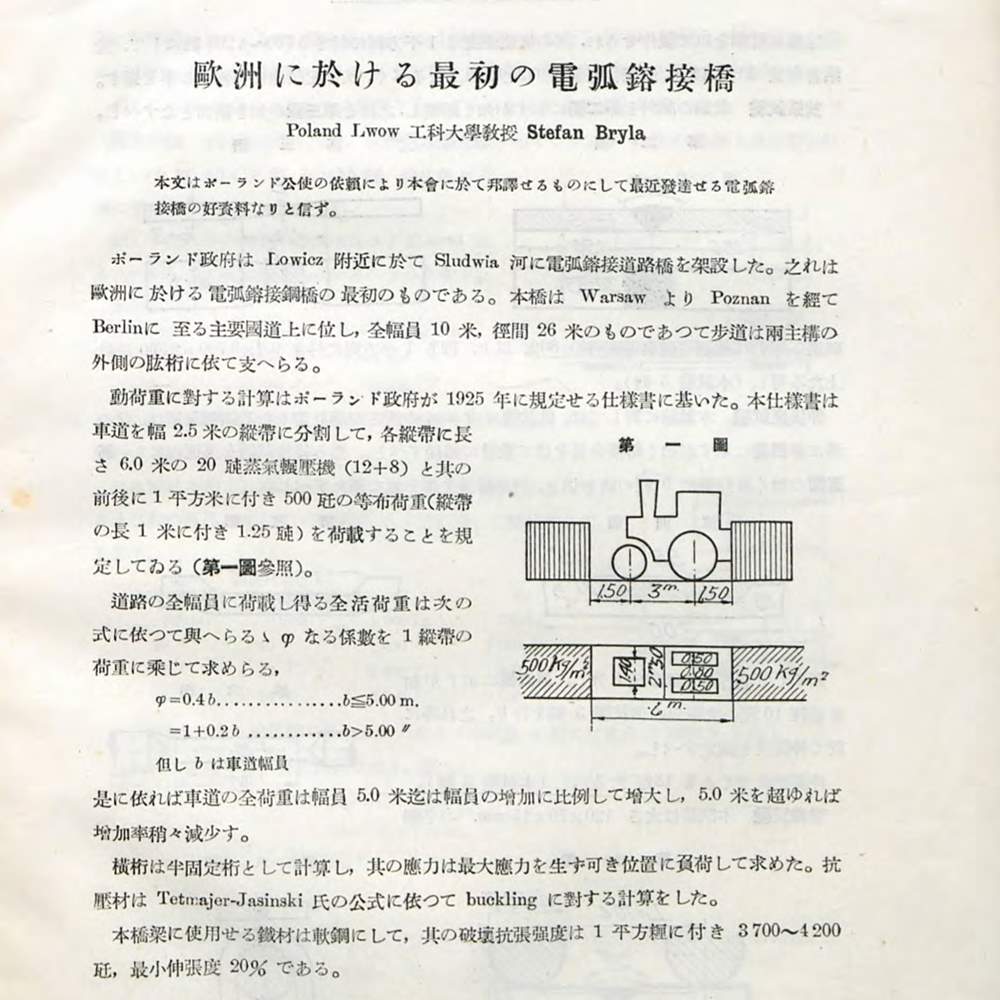

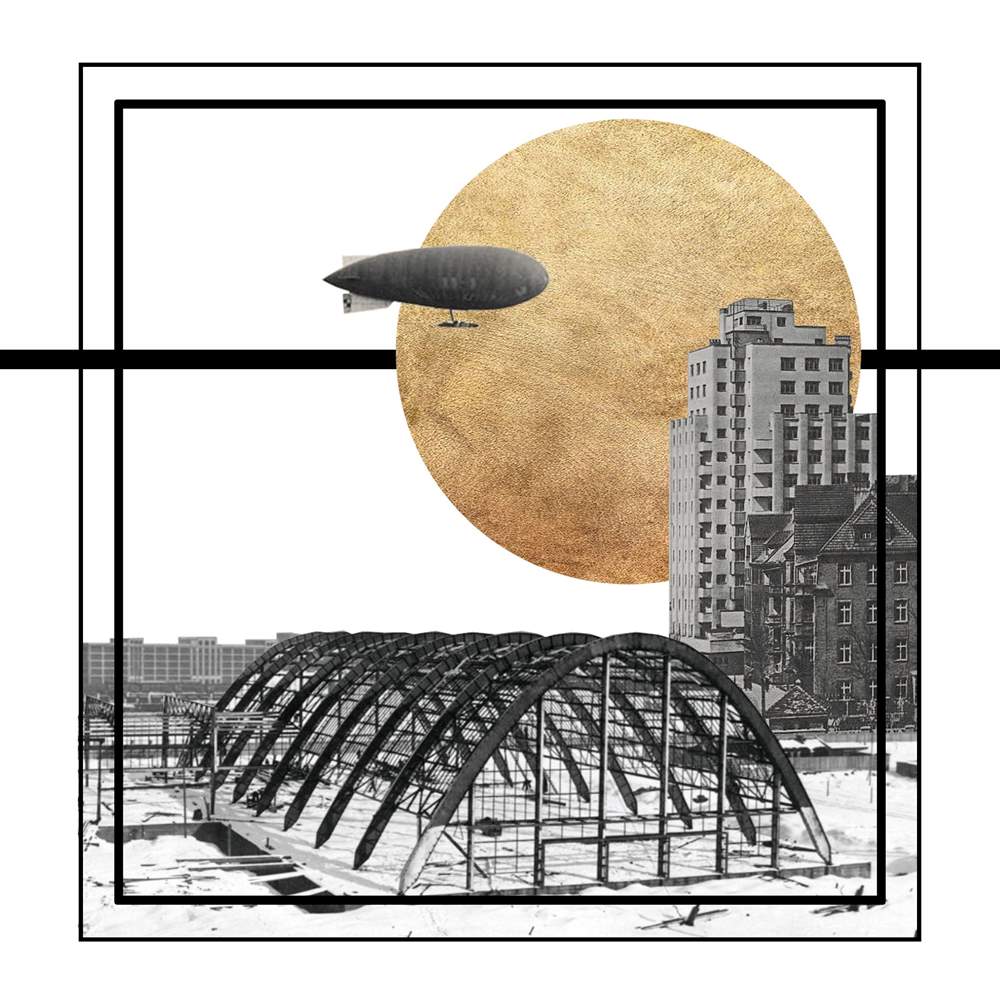

In 1929, Stefan Bryła built the first welded road bridge in the world. The bridge on the Słudwia river in Poland still stands to this day in the village of Maurzyce near Łowicz.

Descriptions of the bridge were published in several languages. It was a paradigm shift in the global technology of steel construction.

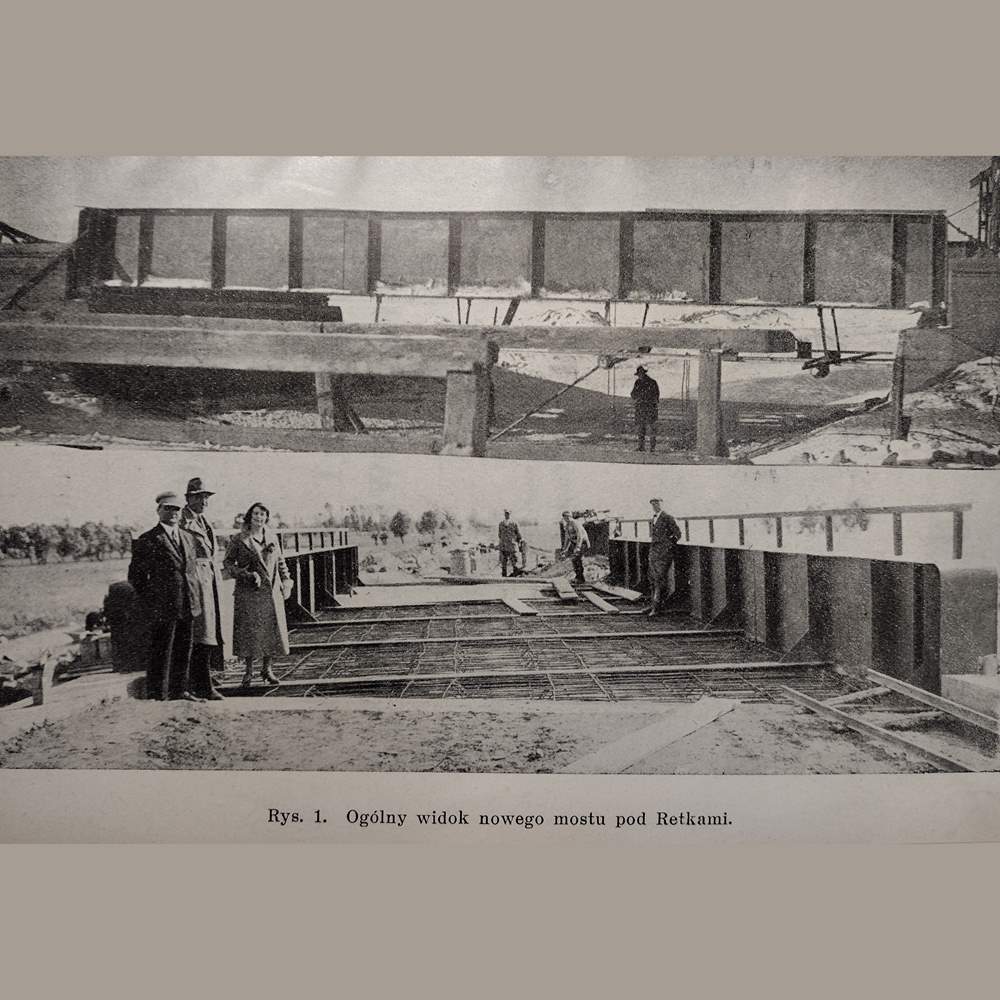

The lands around of Łowicz was a place where Stefan Bryła showcased his engineering skills. In a short time he built another one welded bridge in the neighbouring village of Retki. Contrary to its famous predecessor in Maurzyce, this bridge is in use to this day.

Łowicz is the only city in the world that can boast of having two welded road bridges. One of them is well known and has already occupied a prominent place in the global technical literature, the recently completed second bridge has just been put into service.

Bryła S. (1931). Drugi most spawany pod Łowiczem.

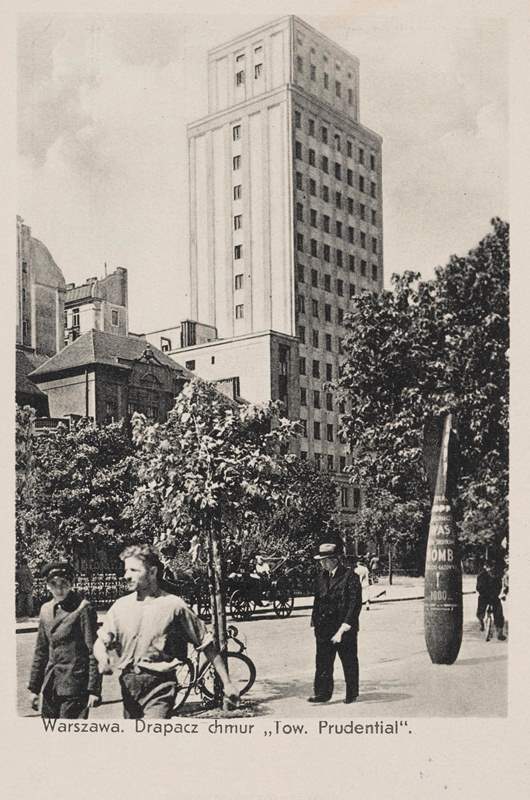

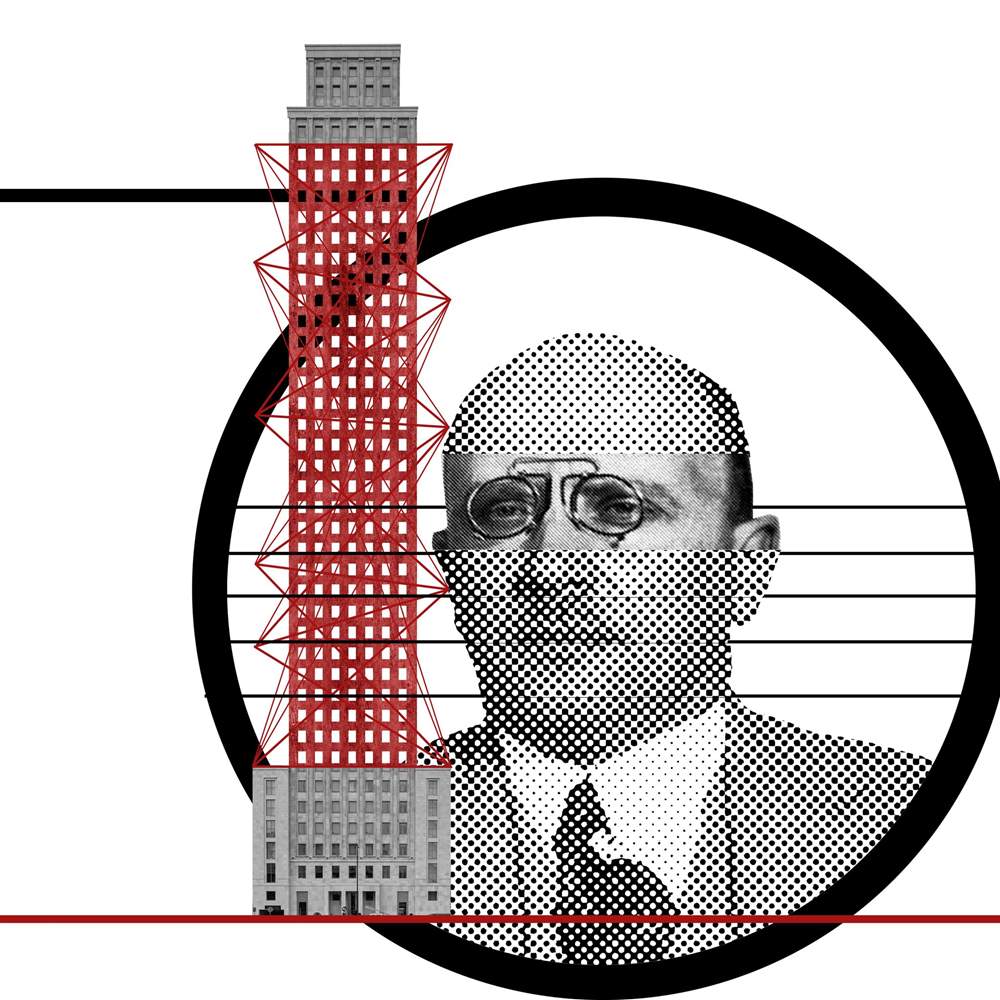

Another piece of Bryła’s work was a sixteen-storey building for the British insurance company Prudential in Warszawa at the Napoleon (now the Warsaw Insurgents’ Square).

The pace of construction was quick, even by today’s standards. The installation of one floor lasted three days. The whole construction of the building lasted three months. Foreign investors accepted welded structural design without objection, claiming that the Poles are more experienced in this technology. (…) The building was burnt during the Warsaw Uprising, and hit by over a thousand shells, but it survived and was rebuilt after the war.

Michałowski, W. (2009). Teki Sarmatów. Link.

This building now houses the 5-Star Hotel Warsaw, in which even teaspoons on the bar are in the colour scheme of the shiny front door. And the doorway – it is better to call it the gate – is lined with brass, just as before the war.

The whole thing was extremely classy. The building’s facade up to the first floor level was made of polished granite, and above it on the street side of the building, it was paved with the sandstone from Szydłowiec. The doorway that led to to the inside of the building was made of patinated brass, and there were sculptures designed by architect Ryszard Moszkowski on the side portals.

Jabłoński R. (2011). Dom wieżowy na placu Napoleona. Życie Warszawy. Link.

It was the first skyscraper in Warszawa, the highest building in Poland, and the second highest building in all of Europe.

When the sixteen-storey high-rise was built for the insurance company Prudential at the Napeoleon Square (now the Warsaw Uprising Square) in 1923-1933, the residents of nearby houses were complaining to the Warsaw authorities that the building was too high, blocking out the light, that it was a blight on the city. People wanted it to be demolished. The skyscraper was 68 meters tall which at the time was the highest building in Poland. (…) In 1936 an experimental TV station transmitter was installed on the roof, it was the time of the first attempts at vision transmission.

Borucki M. (2015). Wielcy zapomniani Polacy, którzy zmienili świat.

There are more buildings designed by Stefan Bryła in the centre of Warszawa, e.g. the National Museum, the All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions building at Powiśle, the Main Post Office at Świętokrzyska street, and the Navy building at the Monument of the Aviator. He authored also ‘the House without Edges’ which stands across from the Bristol Hotel, and owes its name to Józef Piłsudski:

“Now, gentlemen, build without edges” – Józef Piłsudski supposedly said in 1933, when construction of the building began. The order of Marshal, who was thinking about financial fraud, was misinterpreted by the architect, and he designed a building with rounded corners. [Polish word “kant” has two meanings: of an edge and of a financial fraud]

Urzykowski T. (2019). «Dom bez kantów» jak nowy. Budynek odzyskał oryginalny kolor. Gazeta Wyborcza. Link.

Stefan Bryła also took part in the construction of the Market Hall in Katowice, the skyscraper in Katowice at Żwirki i Wigury street, and the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków. He also built the student residence called “Akademik” at the Narutowicz Square in Warszawa. Now, its proper name is in use to describe every student residence.

The bearing walls of the student residence were built at the Gabriel Narutowicz Square in 1922, and it seemed that the monstrous building provided a counterweight to St. Jacob’s Church, an equally monstrous body situated in an empty space. (…) Interestingly, now commonly used, the word “akademik” replaced “student residence” and it comes from the name of this very building.

Faryna-Paszkiewicz H. Akademik, Ochotnik, 56 (11). Link.

When Stefan Bryła was less than twenty-three years old he became a bridge engineering professor at the Lviv Polytechnic. He was also elected to be a Deputy of the Sejm (Polish Parliament) for two terms (in 1926 and in 1930). After the end of the second term he was appointed professor at the Architecture Department of the Warsaw Technical University.

I had been trying to see professor Bryła for a long time, he would come to Warszawa every once in a while. It hasn’t been easy to see him. (…) After trying in the department a few times, I was nervous that I’d never make it on time, my final exam was approaching. I relieved myself using a swear word. An unknown to me, younger colleague stood outside the door, wearing a pince-nez and reading announcements displayed on a special board by teaching assistants.

‘Why are you nervous?’ he asked me.

‘I have been waiting for professor for a long time, I only have ‘bridges’ exams left, if I don’t pass them this week, I won’t pass examination in time.’

‘Do you know professor?’

‘I have never seen him before, you know that professor Thullie taught us so far.’

‘Let’s go together, I also have some business to attend to.’

We entered, and the colleague was looking around muttering something and then he sat down at the professor’s desk. I knew right away that I had blundered. Watching me, professor asked for my index and signed it, looking amused.

Poniż W. (1963). Wspomnienie o profesorze Stefanie Bryle.

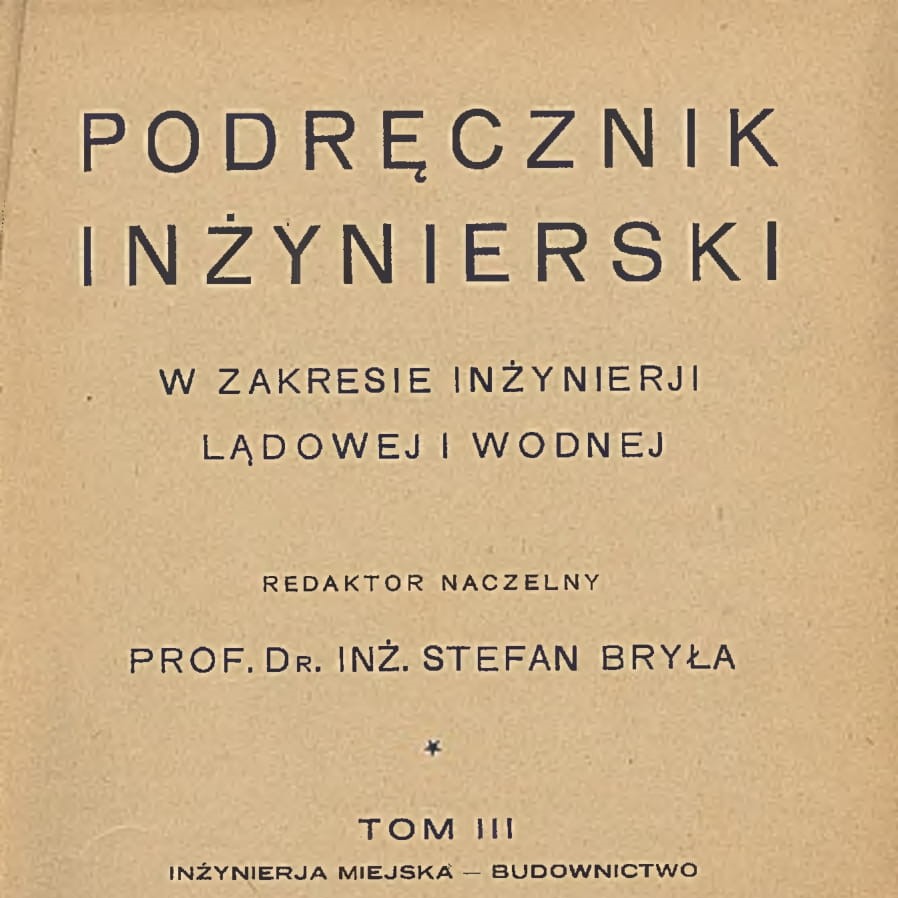

Stefan Bryła wrote a famous four-volume book ‘the Engenering Handbook’, which also was the first Polish encyclopedia of construction engineering.

‘The Engineering Handbook’ was very popular among students and engineering and technical staff. Commonly called ‘Bryła’s book’ or just ‘the Bryła’ it was constantly updated also during the German occupation, and was intended to be republished after the war.

Bielska A., Bielski M. (2011). Przypadek profesora Bryły. Przegląd techniczny. Gazeta inżynierska. Link.

He was engaged in a large number of activities and only his secretary, an old lady, was well-versed in them. Malicious people have even claimed that she was the only reason Bryła knew where and when he taught or where and with whom he had a date…

(2011). Giganci Nauki PL. Polscy wynalazcy, odkrywcy i pionierzy nauk ścisłych. W sieci. Link.

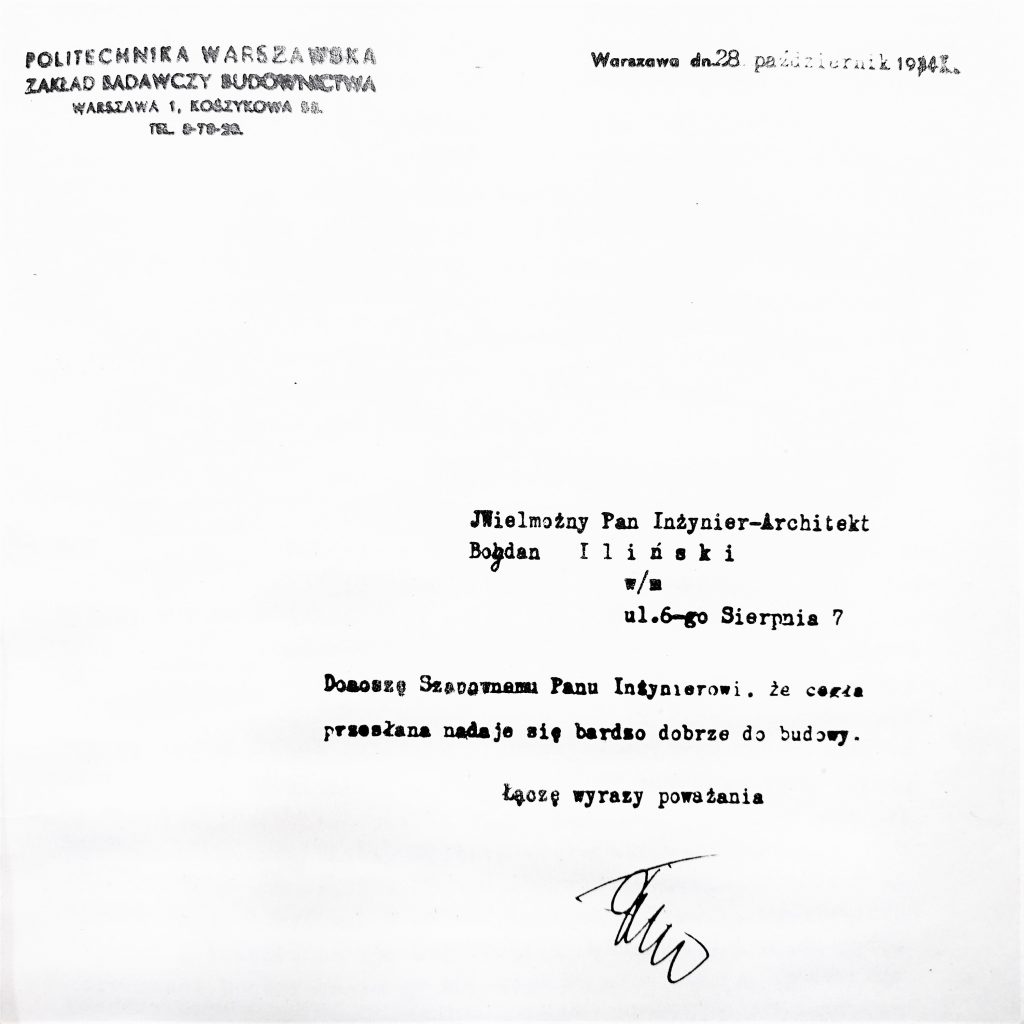

During the German occupation he lectured and examined secretly in his own apartment. The Germans did not allow Polish people to pursuea higher education, and for this reason the Warsaw Technical University officially acted as a technical school of construction. Graduate degrees were coded in a form of a letter of building materials. Depending on the exam result it said e.g. ‘The said brick is suitable for use.’

Professor Bryła prepared a handbook entitled ‘How to demolish welded bridges’ for the Home Army, developed a ten-year plan for the post-war reconstruction of Poland and was the dean of the secret department of architecture at Warsaw Technical University, all at the same time.

75 lat temu rozstrzelany został przez Niemców prof. S. Bryła – pionier spawalnictwa w budownictwie. dzieje.pl . Link.

On the pages of ‘Życie Warszawy’ I was covering baron Ungern’s treasure hunt, an investigative journalism. I got to Melchior Wańkowicz. He lived in a pre-war tenement house at the corner of Rakowiecka and Puławska streets. When he found out that I am a welding engineer, he took me to his office window. You could see the Moskwa Cinema and the gate of the tram depot in the Mokotów district from there. He told me that it is the place where Stefan Bryła was executed.

Michałowski W. (2009). Teki Sarmatów. Link.

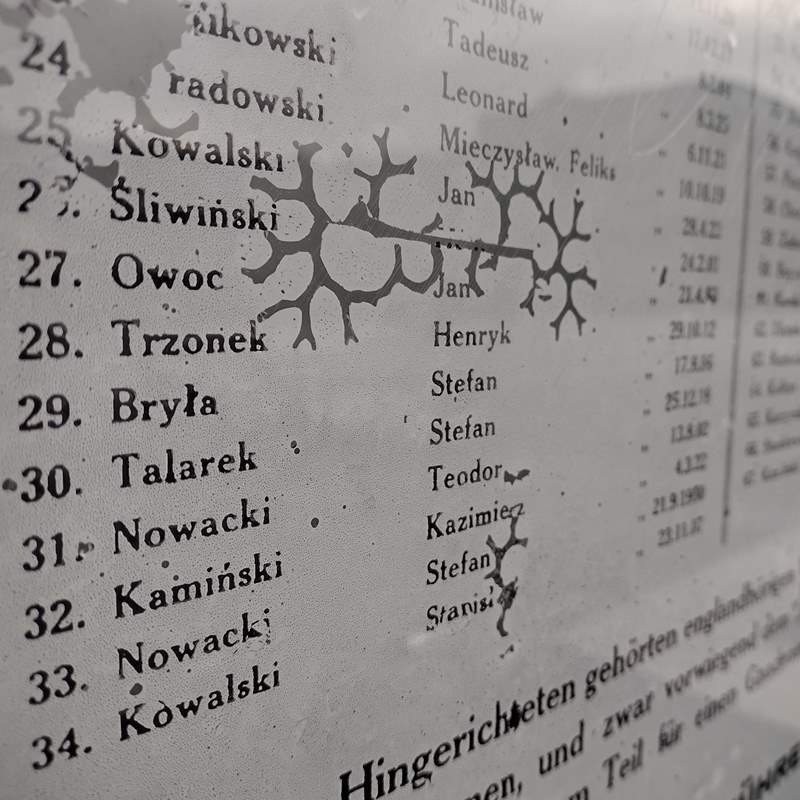

Stefan Bryła was arrested by the Germans in the autumn of 1943 for participating in the underground state. That was his second arrest – previously bail had been posted. This time the Germans shot him two weeks after the arrest. Today, there is a small statue on Puławska street in Warszawa to sixty-seven people murdered at this place by the Germans – including Stefan Bryła.

We believe in the greatness of foreigners in the technical field. Poles have a strange and entirely mysterious to me inferiority complex. This is unjustified and is combined with the absence of criticism directed towards everything foreign to them. But on the other hand, they have a tendency to megalomania.

Bryła S. (1937). Germanizowanie techniki polskiej.

Bibliography and sources:

- „Stefan Bryła”, Katedra Konstrukcji Budowlanych, Warsaw1963.

- Marek Borucki, “Wielcy zapomniani Polacy, którzy zmienili świat”, Warsaw 2015, pp. 26-40.

- Mariusz Grabowski, “Bryła, który chciał po wojnie poruszyć bryłę Polski”, [in:] Polska Times Historia 2019, link.

- Stefan Bryła, „Germanizowanie techniki polskiej”, Warsaw 1937.

- Stefan Bryła, “Drugi most spawany pod Łowiczem”, Warsaw 1931.

- “Stefan Bryła. Innowacyjny konstruktor mostów i wieżowców”, Polskie Radio, link.

- Anna Bielska, Marek Bielski, “Przypadek profesora Bryły” [in:] Przegląd techniczny. Gazeta inżynierska 2011, Link.

Graphics and illustrations: Małgorzata Bochniarz-Różańska, Cecelia Marcheschi

Photos: Przemek Wojenka, Janek Hanuszewicz, Wojtek Marczak, Filip Jegliński

Text: Filip Jegliński

English version: Gabriela Magiera, Philip Steele