Ernest Malinowski: National Hero of Peru who built the highest railway in the world

Indeed, the famous work of the Pole is part of the devoted fight against all kinds of barriers that nature puts between people, both physical and economic. The universe of free movement will replace now the closed and limited world of the colonial era.

Nicolás de Ribas, “El tren de Lima a la Oroya: Construcción e idea de progreso en el proyecto ferroviario transandino del ingeniero polaco Ernesto Malinowski”, Itinerarios 14/2011, pp. 2-3.

He was born in Volhynia, probably in January 1818. His father, Jakub Malinowski, fought in the Napoleonic army and took part in the campaign against Russia, and several years later in the November Uprising of 1830-31 against the tsarist rule of Poland. It is unknown exactly what Ernest was doing then, but the uprising was certainly one of the reasons for his emigration to France.

Malinowski’s participation in the November Uprising “seems to be confirmed by two pieces of information, the first of which comes from an article published in the Peruvian journal «El Comercio» after the death of the Polish engineer. An unknown author writes that Ernest Malinowski answered all questions about the November Uprising only with a sad smile. However, once he told his friends about how he barely managed to escape from the manor house, suddenly surrounded by the Russian army, and about the night he spent in a peasant cottage.

Danuta Bartkowiak, “Ernest Malinowski. Konstruktor kolei transandyjskiej”, Poznań 1996, p. 60 – based on the article “Don Ernesto Malinowski” in Peruvian journal „El Comercio” of March 2, 1899.

Ernest Malinowski left for France with his father and brother, while the rest of the family stayed in Volhynia. Malinowski graduated from high school in Paris, attended the Polytechnic School and the prestigious School of Roads and Bridges, from which he graduated with honors. For several years he was building roads and railroads and regulating the flow of rivers in France and Algeria. He returned to Poland when he learned about the Krakow Uprising of 1846, but did not manage to take part in it.

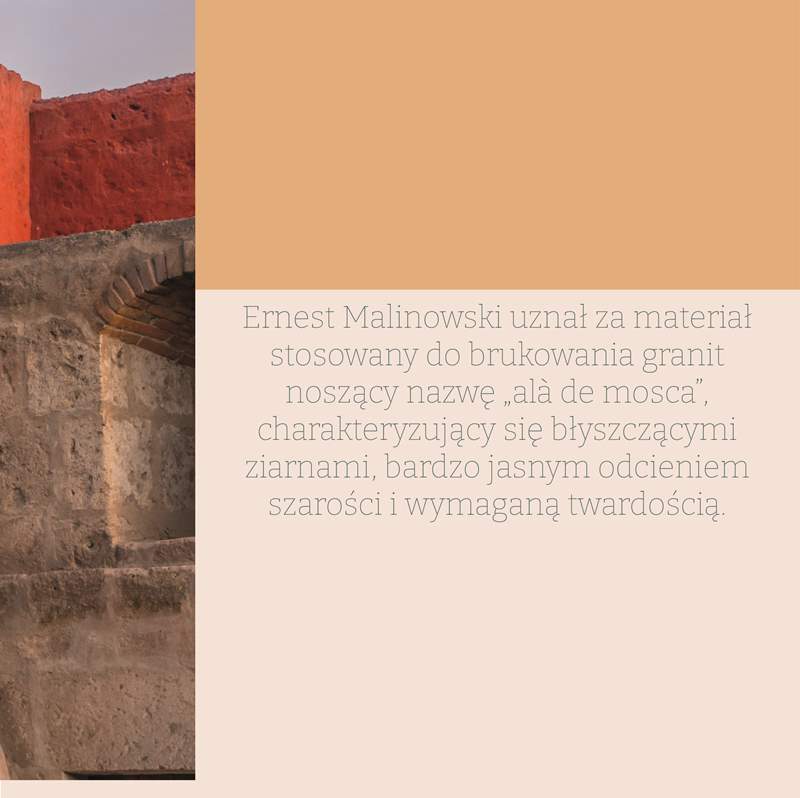

In 1852, he signed a contract for engineering works and education of young people in Peru. One of the tasks entrusted to Malinowski by the Peruvian authorities was the repair of cobbles in the city of Arequipa, famous for its beauty, but destroyed during the war with the Spaniards.

The main problem was the selection of the right material: a hard enough stone, the color of which harmonized with the colonial architecture of the «White City». (…) For the purpose of planning of repair of cobblestoned streets in Arequipa, was needed, not only a great specialist but also a man who could select in the laboratory the appropriate type of material with required characteristics. This task was entrusted to Ernest Malinowski.

Danuta Bartkowiak, “Ernest Malinowski. Konstruktor kolei transandyjskiej”, Poznań 1996, pp. 148-151.

Ernest Malinowski found a granite called “alà de mosca” that was suitable for paving the streets of Arequipa. The stone was characterized by shiny grains, a very light shade of gray, and the necessary hardness.

A few years later, the Peruvian authorities entrusted Malinowski with the task of fortifying the Callao port, located near the capital of the state – Lima. Malinowski had to move fast, because the warships of the most powerful fleet in the world were already sailing towards the port. The Spaniards wanted to regain control of their former colony.

The family name of Malinowski, or rather his nationality, directly contributed to building the confidence of the Peruvians they thought that a Pole would be able to perform miracles in the fight for his or someone else’s independence, in defense of freedom, and in a good cause.

Władysław Folkierski, “Ernest Malinowski i kolej przez Kordylierę Andów”, [in:] “Czasopismo Techniczne” nr 10, Lviv 25 V 1899, p. 118.

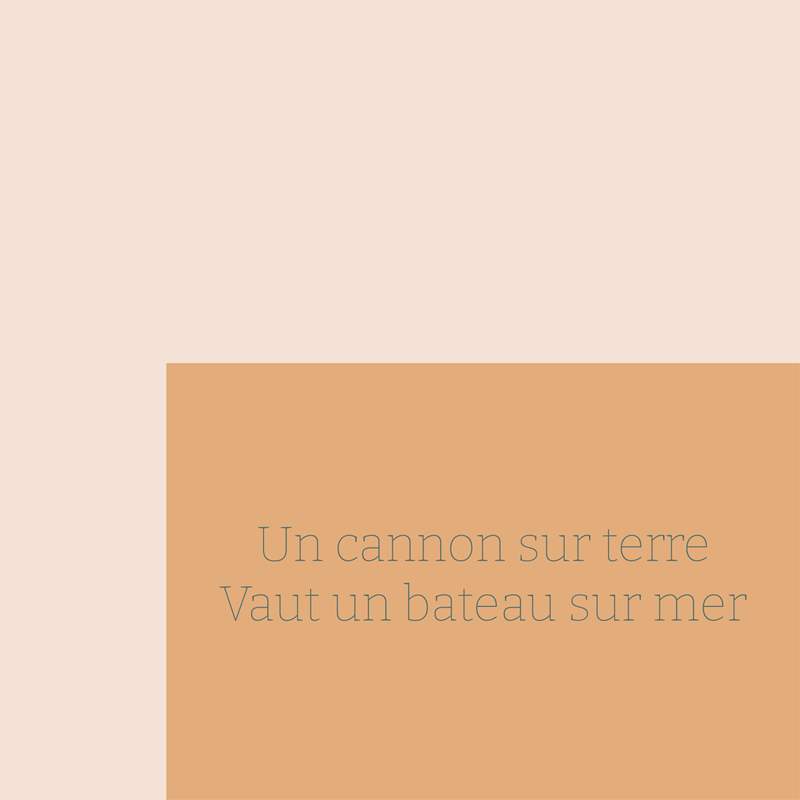

Ernest Malinowski certainly knew and decided to adopt in Peru the motto of the “Gallic” coastal artillery (…) which read as follows: «Un cannon sur terre vaut un bateau sur mer» which literally means that “a cannon on the shore it is worth a ship at sea”, and more precisely that one cannon – especially when it has been skillfully hidden and protected – is a dangerous and formidable opponent for the warship.

Cezary Nałęcz, “Przyczynek do biografii Ernesta Malinowskiego: na marginesie książki Stanisława Łańca «Polska myśl techniczna XIX i początków XX stulecia w kraju i na świecie. Inżynierowie dróg i mostów»”, [in:] “Echa Przeszłości” nr 6/2006, p. 285.

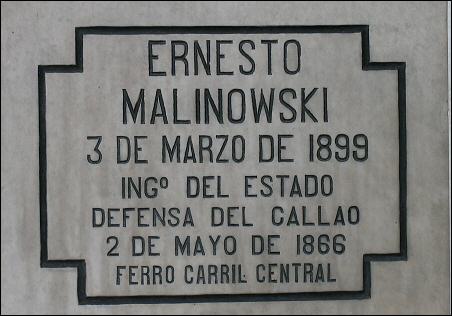

Malinowski quickly brought artillery from the USA, which were placed on the rocks and hidden, while on the seashore the fortifications were built. On May 2, 1866, he commanded the defence of the coast and won a great victory over the Spanish army. For these merits Malinowski was granted honorary citizenship of Peru and the Peruvian government awarded him the title of National Hero (article about Malinowski in the Peruvian newspaper «El Comercio» available here).

Rafael Monleón y Torres, “El combate de El Callao”, oil on canvas, 2nd half of the 19th century.

Many years later, in one of the articles about Malinowski, which appeared in the leading Lima journal “El Comercio”, we read that none of Malinowski’s works provided him with a more important reason for national gratitude than the construction of fortifications and the defense of the Callao port during the battle of May 2, 1866. From that time, as a journalist of “El Comercio” wrote: “Malinowski granted the right to be recognized as a citizen of Peru”.

Danuta Bartkowiak, “Ernest Malinowski. Konstruktor kolei transandyjskiej”, Poznań 1996, p. 184.

Peru had one fundamental economic problem: the high Andes mountains isolating the populated coast from the fertile land in the continent’s interior. Ernest Malinowski proposed to build a railway crossing the mountains to solve this problem.

The idea was criticized as impossible and absurd, firstly by Peruvian experts, and later also by specialists from England and France. The work was not started until ten years after the approval of the Peruvian Congress and an investor was found. This happened on January 1, 1870.

Think about it: Rysy – the highest peak in the Tatra mountains – is 2499 m high, and Malinowski worked at a height almost twice as high, breaking rocks, bringing up beams, railway sleepers, and rails up to the top of Andes mountains, where he was building a rail line.

Professor of technical sciences Ryszard Tadeusiewicz, about Ernest Malinowski in: Marek Bielski, “Rok inż. Ernesta Malinowskiego”, [in:] “Przegląd Techniczny – Gazeta Inżynierska”, nr 16-17/2018, available here.

He was literally everywhere. He ordered to be lowered by rope down into the abyss in order to test the strength of the soil where the bridge pillars were to be placed. He climbed inaccessible mountain peaks like an alpinist to solve detailed technical problems and manage the construction works. He spent the nights in a tent on mountaintops, where the temperature in the morning drops to -14° C, while by noon the heat reaches 26° C. Together with the workers he endured snowstorms and the burning rays of the sun.

Zbigniew Bielicki, “Wyżej niż kondory”, [in:] “Poznaj Świat” R. XXVIII, nr 9 (334), september 1980, s. 3-3-7.

Malinowski managed the construction works himself and was helped by his students. Soon arrived many other Polish engineers who had to flee Poland after the defeat of the January Uprising of 1863-64.

Many new solutions were used in the construction works, because the European methods which had been effective in the Alps were often not suitable in the conditions of the high South American mountains:

What is interesting and shows the ingenuity of Polish engineer combined with great organizational skills, was that he hired sailors – people adept in operating sails and climbing ropes. Their capacities made important contributions to the assembly of the bridges. (…) It is worth mentioning that both during the assembly of the «Verrugas» bridge as well as the other ones, he was helped by the local Indians. He used to hire them when work required a great amount of agility. For example, in order to construct a suspension bridge (a «hammock bridge») the Indians used a slingshot to throw a thin rope to the other side of the chasm, then a thicker rope was pulled with this one, and finally the steel cable.

Danuta Bartkowiak, “Ernest Malinowski. Konstruktor kolei transandyjskiej”, Poznań 1996, p. 219-220.

35 tunnels with a total length of circa 5 km were built, as well as around 20 bridges. The highest one, Verrugas, rests on iron pillars with a record height of 77 meters.

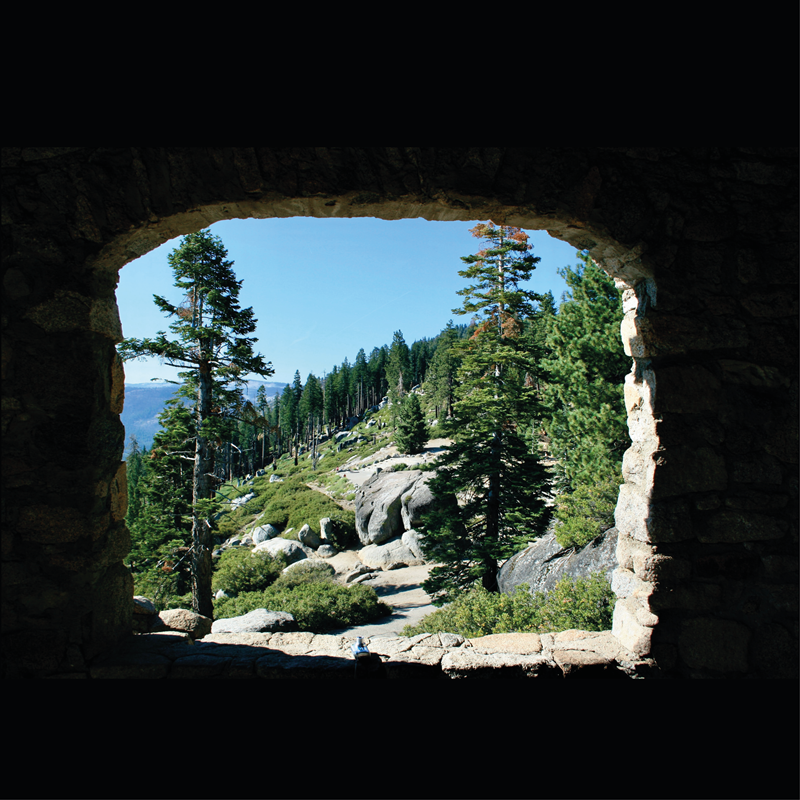

(…) through the western slopes of the Cordillera there are numerous tunnels, sharp curves, and dropoffs as well as double changes of direction. In this part of the railroad, various «railway» records were broken: the longest tunnel (1,177 m) at the highest altitude in the world (4,781 m above sea level), the highest railway junction in the world (4,818 m above sea level).

“Centralna kolej transandyjska”, the article about the Central Transandine Railway on the website of the Polonika Institute is available here.

All the bridges were made of iron, riveted, and most often supported on stone pillars, although there were also some, such as the 200-meter-long «Verrugas» bridge of the Fink system, resting on pillars circa 80 meters high made of wrought iron bars. This bridge, ordered from the factory “The Baltimore Bridge Co.”, was repeatedly described in the contemporary specialized literature as an outstanding achievement of technology.

On the basis of a project considered by experts to be unrealizable, Malinowski built the Ferrocarril Central Andino (Central Trans-Andean Railway): railway line that is used till this day and which reached the highest point in the history of the railroad at that time (it was surpassed only by the Tibetan Railway, which was opened in the Himalayas at the end of the 20th century). The work was completed in 1908, after the death of the Polish engineer, with the line reaching a final length of 346 km. In Europe, many had doubted or questioned the very existence of the Central Trans-Andean Railway, so representatives from European countries were invited for a ride along the railway, in order to clear up any and all doubts.

The railway sleepers were also of the best quality: made of durable red California pine. Ernest Malinowski believed that only by using the most durable materials and involving the best specialists can the success of the entire project be ensured.

Danuta Bartkowiak, “Ernest Malinowski. Konstruktor kolei transandyjskiej”, Poznań 1996, p. 225.

Malinowski founded in Lima the first polytechnic school in Latin America – the Special School of Civil and Mining Engineers – with the help of Polish engineers who had come to Peru. As the director of the polytechnic school, Malinowski began to publish scientific and technical journals founding the Peruvian Annals of Engineering Structures and Mining (Anales de Construcciones Civiles y de Minas del Peru). He helped the government to develop modern mining law, introduced the metric system, and was one of the founders of the Peruvian Geographical Society. He died in 1899 and was buried in Father Maestro’s cemetery in Lima, alongside heads of state and Peruvian national heroes.

In 1999, exactly one hundred years after Malinowski’s death, a monument in his honor was erected on the Trans-Andean railway route. The monument was placed in a symbolic location – the mountain pass Ticlio – at the highest point on the route (4,818 m above sea level). The monument by Gustaw Zemła was carved in granite from Strzegom in Lower Silesia (more about it here).

Photo: Elżbieta Dzikowska, image source here.

In 2018, a mural by Rafał Pisarczyk was unveiled in honor of Ernest Malinowski at the National University of Engineering in Peru (video with a presentation available here, article on the website of the Peruvian Ministry of Foreign Affairs here).

Image source here.

The enormous popularity of Ernest Malinowski during his life in Peruvian society, as well as the recognition of his knowledge in Peru and abroad, may suggest that there were many historical publications about him. Unfortunately, the opposite is true. There are no encyclopedia entries on Ernest Malinowski in any of the contemporary editions of foreign encyclopedias such as Encyclopedia Americana, Encyclopedia Britannica, Enciclopedia Italiana, Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Larousse, or the Bolshaya Soviet Encyclopedia. The only foreign publications with quite brief and inaccurate biographies of the Polish engineer are papers published by representatives of the Polish Diaspora (…) However, no monograph on Ernest Malinowski has been written, and the passing of time has overshadowed the memory of him to such an extent that his life’s work – the Trans-Andean Railway – is attributed exclusively to H. Meiggs [the investor]. Today, even in Peru, where he worked for most of his life, only few people know who Ernest Malinowski was.

Danuta Bartkowiak, “Ernest Malinowski. Konstruktor kolei transandyjskiej”, Poznań 1996, pp. 9-10.

Bibliography and sources:

- Danuta Bartkowiak, “Ernest Malinowski. Konstruktor kolei transandyjskiej”, Poznań 1996.

- Zbigniew Bielicki, “Wyżej niż kondory”, [in:] “Poznaj Świat” R. XXVIII, nr 9 (334), September 1980.

- Marek Bielski, “Rok inż. Ernesta Malinowskiego”, [in:] “Przegląd Techniczny – Gazeta Inżynierska”, nr 16-17/2018, available in whole here.

- Cezary Nałęcz, “Przyczynek do biografii Ernesta Malinowskiego: na marginesie książki Stanisława Łańca «Polska myśl techniczna XIX i początków XX stulecia w kraju i na świecie. Inżynierowie dróg i mostów»”, [in:] “Echa Przeszłości” nr 6/2006.

- Nicolás de Ribas, “El tren de Lima a la Oroya: Construcción e idea de progreso en el proyecto ferroviario transandino del ingeniero polaco Ernesto Malinowski”, Itinerarios 14/2011.

- Władysław Folkierski, “Ernest Malinowski i kolej przez Kordylierę Andów”, [in:] “Czasopismo Techniczne” nr 10, Lviv 25 V 1899 r.

- Marek Borucki, “Wielcy zapomniani Polacy, którzy zmienili świat”, Warsaw 2015, pp. 236-246.

- José Ignacio López Soria, “Malinowski y la ingeniería peruana”, [in:] Ingeniería. Sociedad. Cultura. Publicación del Colegio de Ingenieros del Perú. Lima, nr 1/2006.

Graphics and illustrations: Małgorzata Bochniarz-Różańska

Text: Filip Jegliński

English version: Filip Jegliński, Philip Steele